Play Movie

Listen

to Katherine Kennard

reading this story

MINDFUL SITTING

Zazen Meditation

Morning rain lingers over Ōhara, a bucolic farming village north of Kyoto, its winding streets yet to stir. Thickly forested hills exhale low-hanging mist. A steely sky releases rain in gentle sheets, its ambient patter broken now and then by the call of a lone bird. We are sheltered from the steady flow by the spare, enveloping surrounds of the guest hall of Shōbō-an, a modest Rinzai temple with a four-century history.

Shoes removed at the stone threshold, we kneel on square cushions and take in the atmosphere. Rows of woven tatami stretch across the floor, above which a central lantern casts a mellow glow. Backdropped by the soft sound of water slipping onto stone, the space is charged by the presence of Zen monk Tosei Shinabe. A teacher of Zazen – literally ‘sitting’ (za) ‘meditation’ (zen) – he is here to guide us through the ancient practice, in which the body is held still and the mind brought to attention through breath and posture.

“By simply sitting, you turn your attention inward. By aligning breath and posture, you begin to feel your presence here and now.”

TOSEI SHINABE

Tosei’s warm demeanour and chiselled cheekbones lend his features an ageless clarity. Seated cross-legged on the tatami, wrapped in deep blue linen ceremonial robes, he has his hands resting lightly in his lap. His gaze holds a steady alertness. We lock into it as he guides us into the practice for which we are here today to experience.

Tosei presents Zazen as an open method, available to all. “I see Zazen as a technique of observation,” he says. “What do we observe? Myself, and what is happening around me right now – in other words, reality. By simply sitting, you turn your attention inward. By aligning breath and posture, you begin to feel your presence here and now.”

We straighten our posture and inhale deeply, feeling the firm woven tatami under our folded legs. Thoughts drift in – plans, fragments of conversation, stray memories – yet, as Tosei reminds us, this is not failure. “Even when stray thoughts arise, you do not reject them. You just let them pass.” The practice is simply to sit, observe, and face oneself with full acceptance. “It is about seeing yourself as you are right now,” he tells us, “without judgement, just observing what is there.”

As we continue in silence, some moments feel uncomfortable. Our distracted minds want to lapse. “At times, that can be difficult,” Tosei acknowledges. “But that steady accumulation gradually leads to understanding yourself. And that shapes how you relate to others.”

And so we stay with it. We feel our breath rising and falling. Eventually, it softens. Thoughts appear and fall away. Now and then, a space of stillness opens. Time loses its shape. We feel united within ourselves in this moment, body and mind as one.

“In the rush of daily life, you’re chased by obligations, weighed down by responsibilities. But zazen helps. You start to question why you want things a certain way. You peel them back, and begin to rethink them.”

After a period of time that is impossible to gauge, but turns out to be 20 minutes, Tosei signals the completion of the session with a meditative bow. We move to a side room off the long corridor, where steaming black bean tea is poured into thimble-sized cups. A small arrangement of dried flowers in the corner offsets the textured earthen wall with a dash of brightness. We sink into cushions around a low mahogany table as Tosei begins to share the story of Zazen and how the path drew him in.

Zazen sits at the heart of Zen Buddhism, tracing its origins to the Buddha, Shakyamuni, who attained enlightenment beneath the bodhi tree in the 5th century BCE, in India. Passed from master to disciple, the practice travelled through China and into Japan, evolving into what we now recognise as Zen.

“From the beginning, Zazen has been valued above scholarly knowledge as a means to grasp reality,” Tosei shares. His voice is expressive, measured yet lively in tonal range. He speaks precisely, often pausing to choose his words with care. A naturally skilled orator, he holds our attention, his focused presence instilling the sense that he is entirely with us. “You practice with your own body, grounding yourself in reality, and, in doing so, grasp something essential for yourself."

In recent years, he has observed a growing interest in this ancient practice. People from all walks of life are seeking out Zazen as an antidote to scattered attention and the noise of modern life. Especially for those primed for constant striving, it offers a radical paradigm shift: there is no goal, no promised result – just observing what is.

“In the rush of daily life, it can be hard to know what we are really doing,” he says. "There’s rarely time to slow down and really think about what you want to do." Emotions go unexamined, reactions pass unnoticed, as we move from task to task. “You’re chased by obligations, weighed down by responsibilities – and that’s fine in its own way,” Tosei continues. He speaks steadily, his eyes enlivened and his posture composed. “But Zazen helps.” Over time, fixed assumptions begin to loosen. “You start to question why you want things a certain way. You peel them back, and begin to rethink them.”

“My body became very still, my mind cleared. I felt as though something had begun.”

Born in Tokyo in a family with no ties to Zen, Tosei’s early encounters with Buddhism were limited to visits to graves or attending funerals. He studied law, worked for a newspaper, then began to partner with traditional craftspeople across Kyoto. The practice found him later in life through a series of chance encounters.

It was through craftsmanship that he first entered Ryosokuin, a sub-temple of Kenninji, Kyoto’s oldest monastic precinct, where he helped produce a ceramics exhibition. During preparations, the head priest invited him to try sitting. With no particular interest but no reason to refuse, he agreed. The experience surprised him: “My body became very still, my mind cleared. I felt as though something had begun.

“I was nervous about sitting for long periods,” he admits, “but it left a deep impression. I hadn’t realised how valuable time spent facing inward could be. I had always had a vague sense of myself and of what the world might be, and Zazen gave me the sense that it was fine to feel that way.” Essentially, it allowed him to remain with those questions, without needing to resolve them.

What began as an occasional practice soon took hold. Tosei committed to full monastic training. There was no structured curriculum. The head of practice, the ‘Rōshi’, offered no direct instruction. “At the monastery, they didn’t teach Zazen like school,” he explains. “You learned by observing presence.”

Days unfolded through repetition: sitting, simple tasks, attentiveness to each moment. Trainee monks sat from four to a maximum of 20 hours a day. “I learned by simply practising Zazen and living each day with great care, paying attention to the smallest details and acting with compassion. These two things formed the heart of my training every day.”

Cooking, cleaning, laundry, tending the garden – “everything was done precisely, punctually, without making noise, and in sync with those around you,” he says. Blades of grass were hand-plucked individually from the monastery garden. “That level of attention made the work demanding.” Through this life, small shifts gradually occurred. “You noticed your own habits, your reactions with others.” The most valuable learning, he says, came in those moments of observation.

“In the world of Zen, the temple you belong to is not important. It isn’t even about which religion you follow. What matters is how you live as a person.”

Having graduated after three years of training, Tosei returned to Ryosokuin, where he lived and taught for the next five years, welcoming thousands of visitors to experience Zazen. His days were guided by responsibility and routine: hosting Zazen sessions for the public, cleaning, welcoming guests, and preparing ‘goshuin’ – the calligraphic inscriptions offered to temple visitors.

Over time, his sense of purpose crystalised. “I decided to focus on teaching Zazen, and step away from the demands of temple management,” he recounts, adding that he sees religion as “a story about how we view the world.” Affiliation holds little weight for him. “In the world of Zen, which temple you belong to is not important. It isn’t even about which religion you follow. What matters is how you live as a person.”

It is at Ryosokuin that we meet Tosei again a few mornings later. With permission, Tosei has invited us to join him for another session. Wearing his formal linen robes, he walks along the stone path, his wooden clogs clicking gently.

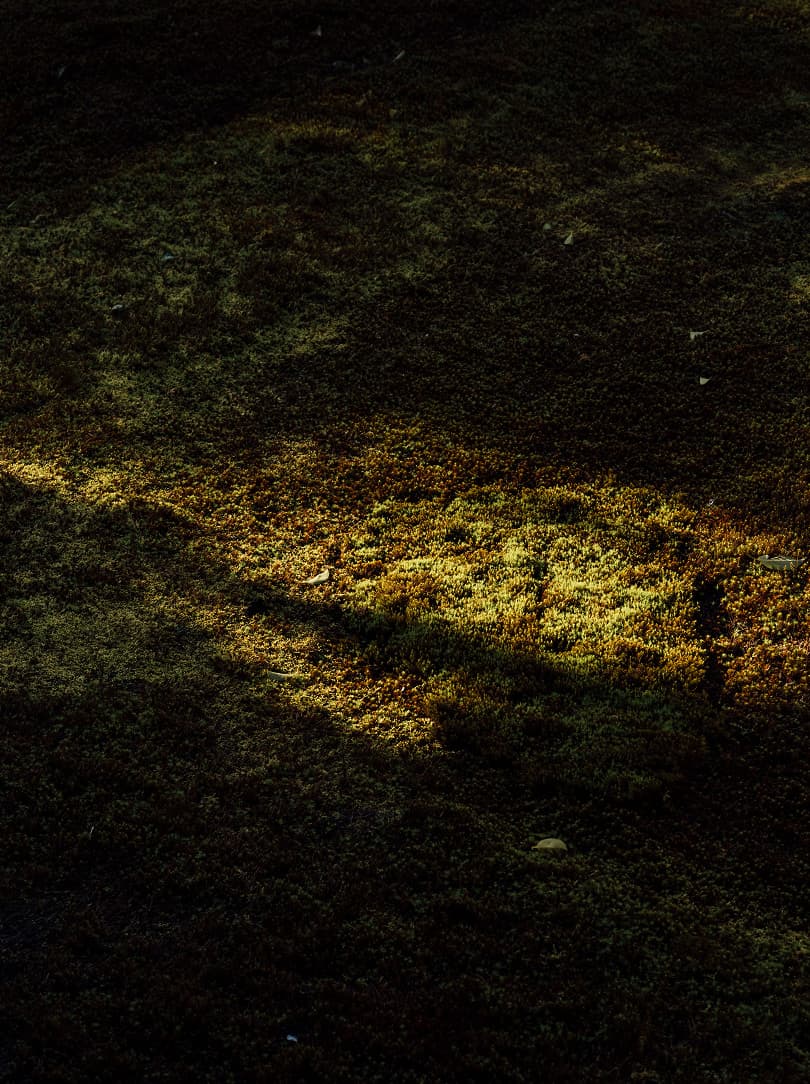

At 5am, the air is crisp. We walk the diamond-shaped stone paths of the forecourt garden, an ethereal landscape of white gravel and carefully raked patterns, pockets of soft moss, weathered stone basins, and a scattering of deep green trees.

We take off our shoes and step onto the dark-wood veranda, which creaks softly beneath us. The guest hall we enter carries a reverent energy, its golden tatami bordered with intricately woven bands. Muted morning light, the day’s first rays, begins to seep in across the floor. Tosei motions for us to take our places kneeling on the tatami across from him. In front of him, he sets out a few objects: slender wooden incense boxes, a brass bell, driftwood, a clay dish, a long wooden stick smooth with use.

With a single, fluid motion, he lowers himself onto a ‘zafu’, a small round cushion, which disappears beneath the elegant drape of his robes. Seated cross-legged, he faces us directly, hands resting in his lap. He deftly lights a match and holds it up to a slender stick of incense that he created together with his friends at Sanga Incense Lab. The incense has a 20-minute burn time – ideal for a beginner’s session. The scent rises, a thread of hinoki and sandalwood. He dings a small bell to clear the energy and focus our attention. The space settles. We begin.

“When your posture settles, your mind calms. With a calm mind, you notice subtle changes. You begin to notice many things – sensations, cycles, thoughts. It’s about getting to know yourself.”

When new students come to sit with him, Tosei emphasises first principles. “Simply take some time to stop,” he says. “That alone lets you notice all sorts of things. You don’t need to worry about posture or small details.”

Simplicity also shapes how he introduces posture. “Zazen is very accessible. You can sit on a chair if you like. You can kneel or sit cross-legged. Any posture is fine. What matters most is the posture of stopping and observing. That alone leads to discovery.”

Overthinking can be counterproductive. “Posture is meant to create a comfortable state. If you can achieve a stable and relaxed state, that’s enough. There are detailed ways to do it, but if you focus too much on them, you might neglect the really important act of observation.”

Breath works in much the same way. “Breathing can be somewhat controlled by your will. By using it skilfully, it can help calm both body and mind.” He encourages an easeful approach. “I think it’s best to breathe freely and comfortably. There are special breathing methods, but basically, the most comfortable breathing for you is what I recommend. As long as you keep breathing in the way that feels most natural to you, that’s all you need.”

In Zazen, the corporeal leads the cerebral. “When your posture settles, your mind calms. With a calm mind, you notice subtle changes. That sparks exploration.” Over time, sitting reveals what often passes unnoticed. “You become aware of many things – sensations, cycles, thoughts. It’s about getting to know yourself.” From there, attention begins to open outward. “You observe the small changes happening around you – the grass swaying, a bird chirping. You even begin to register things that seem completely ordinary. By observing closely, I believe you come to many different realisations.”

As we follow his instructions, settled into a smoother pace of breath, we notice a small ‘kekkai’ boundary stone, its presence drawing us back to attention. Crafted by Tosei, the stone comes from Awaji Island, its rough surface bound with a band of rare Japanese hemp that is traditionally used in Shinto ritual.

Typically placed to mark thresholds in temples and tea houses, kekkai stones are deeply linked to Zen philosophy, embodying the notion that ‘heaven, earth and I all share the same origin, and are therefore one’. Held in the palm or glimpsed in passing, the coarse stone and smooth hemp – more precisely, the hemp rope’s slow but inevitable decay – serve as a reminder that we are never separate from the world around us. The boundary is an illusion.

“Using discomfort as a clue to begin a line of inquiry is something often done in Zen practice. When you feel it, ask: What is this sensation? What is this mood? That’s when inquiry begins.”

For many beginners, the greatest challenge is simply continuing. “Most people quit because they expect clear, immediate rewards that don’t materialise,” Tosei says. Yet in Zazen, sitting with discomfort is part of the practice. He suggests welcoming it as a subject for exploration. “Using that discomfort as a clue to begin a line of inquiry is something we often do,” he explains. Whether arising in the body or the mind, each sensation, each mood becomes part of the sitting. “When you feel those things, you ask: what is this sensation? What is this mood? That’s when inquiry begins.”

He shares a personal example. “There are moments when I notice my own prejudice. Why? Because I am no different from a single mosquito or a blade of grass – just one living creature among many. I keep trying to observe myself from above.” Through the act of observation, a broader perspective emerges.

The aim is not to erase bias entirely – as he acknowledges, “a state entirely free of prejudice cannot exist,” – but to live with a clearer view of it. “Understanding that such a state cannot exist and continuing to live with that awareness is, I think, what really matters.”

A deeper shift in perspective begins with how we relate to reality itself. In contrast to conventional Western thought, where reality is often seen as something to analyse, control or improve, it is viewed in Zen as simply: what is. The shift lies in learning to meet reality without resistance, to witness rather than manipulate. “Exploration begins with accepting reality as it is without looking away,” Tosei says.

Zazen offers a way to face this more clearly. “What I see with my own eyes – what’s happening around me – is the only certain thing. Accepting or surrendering to reality means trying to observe it and understand it. You have to accept reality, but because you can’t always do that, inner conflict inevitably arises. That’s the difficulty of it. But accepting reality is a very important attitude.”

“To really see what’s happening in front of you right now – that might be the true beginning of Zazen.”

Rather than abandoning one’s judgement or being swept along by circumstance, Zen holds that accepting reality is about meeting the present moment with clarity. “To really see what’s happening in front of you right now – that might be the true beginning of Zazen,” Tosei observes.

Zazen, in this way, becomes a way of learning to live with greater steadiness in the midst of what is. “Whether we’re aware of it or not, truth is always there,” as Tosei puts it. “Sitting quietly and engaging in exploration increases the chances of noticing it.”

Over time, Zazen can shape how we relate to life at large. For Tosei, the heart of the practice is this: to realise we are not separate from the world, but integrally connected to it. “The most important thing, I believe, is to realise again that the world and the self are one,” he says, choosing his words carefully. “When you say ‘the world and the self are one,’ it can sound a bit inflated, but even something like ‘the self and nature are one,’ or ‘I am part of nature’ – that’s a perfectly good way to understand it.”

“People often think humans are special, or that the self is somehow cut off from the world. There are many people who live in anxiety because of that. But if you calmly observe reality, you’ll notice that’s not actually the case. What I most want to share is this: that this real world and ourselves are one and the same.”

This is something, he feels, many have forgotten. “People often think humans are special, or that the self is somehow cut off from the world. It feels like there are many people who live in anxiety because of that. But if you calmly observe reality, you’ll notice that’s not actually the case. What I most want to share is this: that this real world and ourselves are one and the same.

“It’s a mysterious practice – simple, yet deeply profound,” Tosei says. What I’d like people to realise through practising Zazen is this: that we, from the beginning, are entirely free. It’s not about becoming free – I want everyone to realise they already are.”

The bells of Kennin-ji toll, their resonant tones marking the hour. The light is brighter now, the day starting to warm. Our session draws to a close. Tosei moves lithely around the guest hall, gathering his belongings before leaving the room to change out of his ceremonial robes into an indigo work uniform of soft Japanese cotton. He accompanies us through the quiet temple grounds. At the gate, we depart with a deep bow of gratitude.

A sense of peace lingers in the morning air, a lightness as if something has lifted from our shoulders. Though our time with Tosei has come to a close, he leaves us – like so many – with the tools for a lifetime of practice: sit, breathe, observe. Simple acts that hold profound potential: for stillness amid the noise, for self-understanding, for gradually reframing our way of being in the world. This is the path. That is enough.