Play Movie

Listen

to Katherine Kennard

reading this story

CRAFTING COMFORT

Niwa Futon

Mid-morning spreads a broad haze of pale blue across the sky as we arrive on the fringes of Nagoya. The grey-toned port city pulsates with the creaks and groans of industry that propel Japan’s economy, yet today we are here to witness a process led entirely by hand.

Our destination presents a demure silhouette. The production spaces of Niwa Futon nestle unassumingly into their light-industry landscape. It’s only when drawing close to the soft light of the pint-sized showroom, denoted by a navy strip of cloth that bears its name, that the history and stature of the family-run atelier emerge.

The walls are clad in a right-angled system of light timber slats that cast the room in a radiant glow. On floor-to-ceiling shelves, plump cushions in neutral tones and diverse dimensions are stacked between neatly ordered boxes. Their forms are varied – flat and rectangular, squat bolsters, square and dimpled with a central notch, their perfect corners puckering into sharp edges that define their sculptural feel. Below them, a single mattress rests on a horizontal plinth.

On the facing wall, above an antique chest of drawers on which a small paper lamp and a curvy bonsai rest, a row of glass-framed emperor’s awards is displayed. They bear the signatures and seals of the prime minister of the time, attesting to this family’s continuous mastery of their ‘monozukuri’ – craftmaking – passed down through generations of first-class-certified craftsmen since its founding during the Meiji era, more than 150 years ago.

The fifth-generation custodian of this lineage, Takuya Niwa, emerges between cream-toned ‘noren’ curtains to greet us in beige trousers and a cream shirt, his round tortoiseshell glasses accentuating his spirited expression. There is an agile ease to his manner, an apple-cheeked smile that breaks when he laughs. He invites us to take our place on a slim, square cushion on the bench that encircles the concrete showroom floor.

“The beginning of Niwa Futon was in the cotton beating trade,” he tells us of his family’s story, once formalities have been shared, clarifying that “cotton beating means the work of artisans who make cotton fluffy” – in other words, turning dense bales into the soft fill used by futon makers. It was in the business’s third generation – when Niwa-san’s grandfather took over the business – that futon making was brought in-house, establishing a continuity of raw material processing and object creation that has set Niwa Futon apart from industry convention ever since.

“We procure the raw cotton ourselves, then do the cotton beating and make the futons by hand,” Niwa-san explains. “Normally, factories that produce cotton only produce cotton, and those who make futon are separate craftspeople, but we handle everything from start to finish. This means we take full responsibility, but it also allows us to make very comfortable futons.” For him, this continuity is essential. To prepare the cotton and to craft the futon are one act; to divide them would break the meaning of making.

“In this age of mechanisation, not many people make futon by hand. Yet there are still futon artisans who persist in making them by hand in Japan. I want the world to know such people exist. My mission is to pass on futon to others.”

TAKUYA NIWA

“Japanese futon making is one of Japan’s most traditional crafts,” Niwa-san shares. “But there are very few Japanese futon makers left. In this age of mechanisation, not many people make them by hand. Yet there are still futon artisans who persist in making them by hand in Japan. I want the world to know such people exist. My mission is to pass on futon to others.”

Contrary to the common Western understanding of a futon as a simple mattress, the word futon itself refers to the layered bedding composed of three parts: the ‘shikibuton’ or mattress, the ‘kakebuton’ or duvet, and the ‘makura’ or pillow. Each element holds a role within the cycle of rest. The shikibuton lies directly on the tatami – about 10cm of layered cotton that can be rolled and stored each day. It carries the memory of the body yet always returns to form when aired in the sun.

The kakebuton, lighter and more yielding, rests above, its weight balanced by the breathable cotton. The makura, filled with buckwheat husks, adjusts to the head’s weight and keeps cool through air circulation. Together, they create a complete system – simple, ventilating and in tune with the body’s natural cycles.

Historically, these bedding forms developed from Zen practice. The zabuton, the sitting cushion used in meditation, gave rise to the shikibuton, which extended the same posture into rest. The kakebuton traces its lineage to the kaimaki, a kimono filled with cotton that monks once used for warmth at night.

Futon culture grew from the tatami floor itself. Before cotton arrived in Japan from Southeast Asia in 799, straw mats were the convention. The introduction of the plant, initially to Aichi Prefecture, transformed sleep into a softer art. By the Edo period, futons became common beyond the upper classes, and the act of rolling one’s bedding each morning became part of domestic routine – one that has endured through the ages.

Niwa Futon’s core offering honours this layered history and three-part structure of mattress, duvet and pillow, while translating it into a refined contemporary practice. The shikibuton and kakebuton anchor the range, joined by specialised pieces that extend the same craft intelligence into forms that bridge tradition with contemporary life: the Mawata Futon, combining cotton and silk through the Edo-period fukuro-mawashi method; the compact Ohirune Futon for midday rest; and the Watamakura, filled with cotton and buckwheat husks. Alongside these, the Gorone Makura serves as a travel pillow, while the Kyo-Soku offers a reinterpreted armrest for moments of repose. Like his father and grandfather before him, Niwa-san builds each futon around a gentle arch. This structure allows air to circulate through the fibres and prevents the bedding from collapsing into flatness, as many mass-produced varieties tend to do, due to their synthetic cores or uniform padding.

“Mass production prioritises ease of making by keeping a uniform thickness, which is a completely different approach from ours,” he notes. “Mass-produced futons often contain core materials inside or are made with different substances, whereas we make futons in a kamaboko shape, higher in the middle. As you sleep, it gradually settles and adapts to your form.”

For Niwa-san, a futon is a companion in time, responding to the care invested in not only its making but its maintenance. Customers are encouraged to dry them regularly and vacuum rather than beat them. Every five years, he offers a re-tying and stitching service to maintain each futon’s form and integrity.

“We make futons in a kamaboko shape, higher in the middle. As you sleep, it gradually settles and adapts to your form.”

Niwa Futon’s entire production process takes place across a total of 60 square metres, divided between a two-storey atelier fronted by the showroom. The ground-floor sewing area features a compact set-up for sewing covers, packing and administration. Round the corner, a staircase leads to a tatami-lined, cotton-bale stacked loft, which sets the scene for filling and finishing.

About 10 metres down the road is the micro factory where raw cotton is processed into thick wads, primed for filling into their hand-sewn covers. Gesturing that he will show us the way, Niwa-san tucks a tightly bound bale under his arm. Shoes back on, he leads us leisurely to a ground-floor garage door, which he rolls up to reveal a slender space engulfed by a timeworn industrial machine, waiting to resume its work.

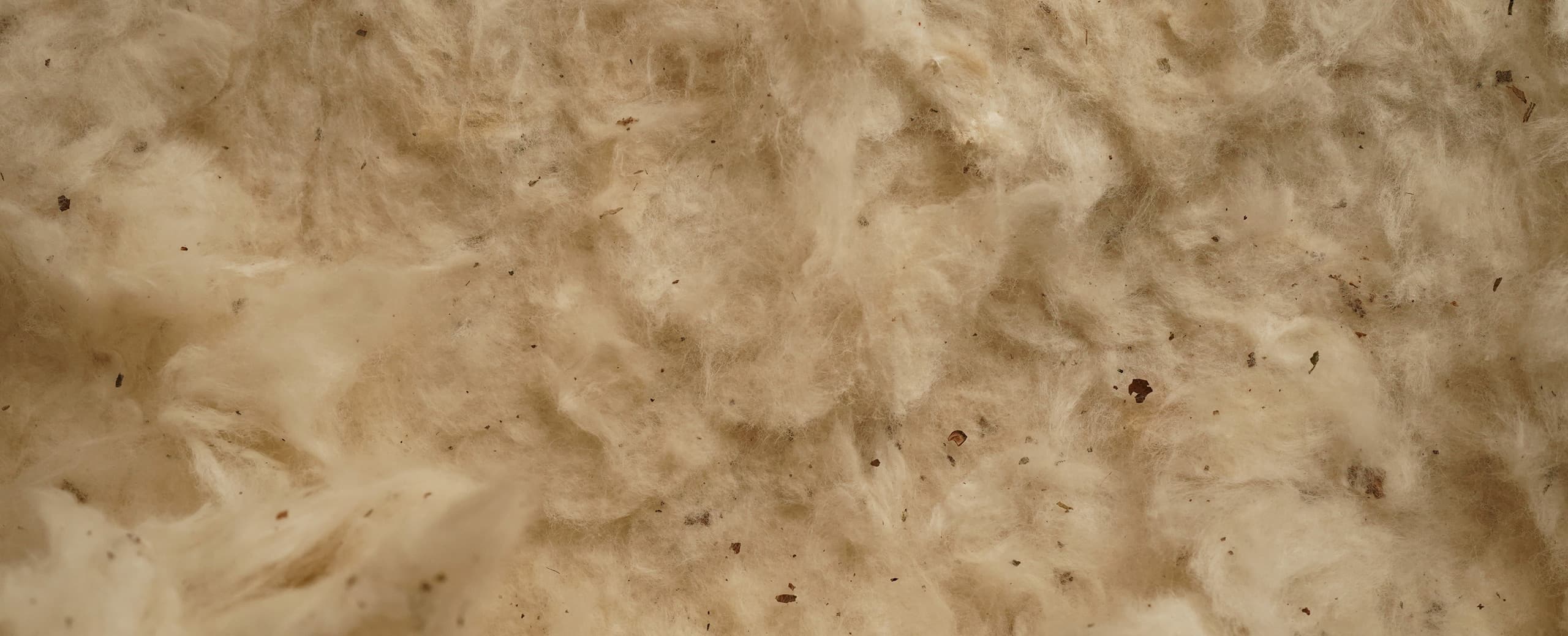

Cotton dust floats like mist, softening the outlines of pipes, beams and machines. A single clock ticks above the doorway, its hands furred with tiny white threads that hang like minuscule stalactites. The remaining floor space is packed with candy floss-like wads of cotton pressed into soft layers that resemble pepper-flecked cream. Niwa-san places down his bale and raps it with his knuckle to show us the hollow sound it makes, before snipping the binding straps. The mass swells and breathes, springing upward as if remembering its natural form. It is scrunchy-soft to the touch.

Niwa Futon works with three types of cotton – a blend from across India, a special variety from its Assam region, and another from Mexico. Each is distinct in fibre and hue – the Indian firm, the Assam dense and grey, the Mexican soft and creamy. To achieve the optimal density and comfort level for his products, he uses a custom blend for each, with ratios affected by season, weather and humidity.

The fine process of calibration is a matter of intuition and feel as much as it is a precise science. For the base-layer shikibuton, he begins with a firmer base before adding softer layers for comfort. “By adding Mexican cotton, I create the right softness, cotton that is suitable for items laid underneath,” he explains. For the top-layer kakebuton, he reverses the blend, seeking suppleness and pliancy.

“Nowadays the cotton blending machines are becoming fewer, and there are no more manufacturers making them. If our machine breaks, we repair it ourselves.”

Standing in the tight nook between springy cotton and unbending machinery, Niwa-san pulls the switch of the old ‘kai menki’ – the machine whose name literally translates to ‘the opening of cotton’ – and it groans into life, wood and iron creaking as if waking from slumber.

He lifts off a cloud-like armful of the crinkly edged Indian cotton plinth and places it on a small green scale, adding more tufts of the softer variety until he has the right composition. He slowly presses the cotton clouds between its wooden rollers. The machine draws it in between slow-turning rollers, pressing and digesting on its conveyor belt before sucking them up through a pipe into a chamber lowered from the ceiling.

The air hums with a muffled cadence – wooden rollers turning, belts straining. As the machine turns, it spits out fine specks of cotton dust, which covers every surface in a fine mist. Wearing a face mask, Niwa-san works closely beside it, reading its mood through sound. “Nowadays the machines are becoming fewer, and there are no more manufacturers making them,” he explains during a pause. “If our machine breaks, we repair it ourselves.” As an insurance policy, the family keeps an entire spare machine in storage, should the existing one become unusable.

This process of ‘wata uchi’ – manual cotton blending – is disappearing, Niwa-san says, but as long as the machine holds, he will keep it alive. We watch as the flattened cotton sheets emerge from the end conveyer, even and smooth. Layer by layer, he gathers and stacks them before preparing them for the next stage by rolling them into tight cylinders. Around us, the air grows dense. Niwa-san winds down the machine, which slowly shudders to a halt, and gently scoops the spongy rolls into his arms.

“I watched futons being made from a young age,” he shares, as we walk back out into the humid air that lingers from the long summer, “but I had never actually made a futon until I was 25, when I learned everything from my father. That was my beginning.”

“I saw that my father’s futon making was a continuous craft, created entirely under his own responsibility. Through that, I wanted to make everything with my own hands, and that led me to this profession.”

Before entering the family business, Niwa-san studied cultural anthropology at university and pursued product design through books and self-led study, as well as working for an electronics manufacturer. The job was stable, but his work felt distant from creation. “I thought a manufacturer meant making things, but in a large company the division of labour is the norm,” he explains. “I saw that my father’s futon making was a continuous craft, created entirely under his own responsibility. Through that, I wanted to make everything with my own hands, and that led me to this profession.”

His intersecting interests in product, fashion and interior design deepened during these years, influenced by Japanese designers whose work balanced tradition with modernity. “Looking at the works of many different people became a source of inspiration for me,” he reveals. That curiosity catalyses him to constantly expand his creative thinking, and explore new products and collaborations in and beyond Japan.

“I feel that my role may be to apply the craft of making futon to new products,” he notes. “I very much want people round the world to see this craft. That is why I seek to refine it further, to draw out such possibilities.” He documents his work on his beloved Leica – photography being another passion – capturing details that might spark new ideas, allowing heritage techniques to be carried forward into contemporary expressions.

One of those expressions takes the form of a set of two meditation cushions – a larger, square zabuton and a smaller, rectangular zafu, created together with Zen monk Tosei Shinabe and AGOBAY. The collaboration began with a question: how can the act of sitting, so central to Zen, be supported through the craft of futon making?

“When I first met Tosei-san, I wondered what I could propose, and I suggested a meditation zabuton,” Niwa-san says. Tosei-san mentioned an older two-layer type he had once used, which piqued his interest. He returned the next day with a prototype, working with the iterative efficiency typical of his preferred process – translating a partner’s brief into something tangible for immediate testing and refinement.

The layered form, with more filling than usual, gave both stability and depth, allowing for long periods of sitting without strain. Through several iteration rounds and a two-month testing period by Tosei-san, the inner firmness of the final design increased by 60 per cent.

“I very much want people round the world to see this craft. That is why I seek to refine it further, to draw out such possibilities.”

Accompanying the zabuton is a smaller zafu cushion that added a new precedent to Niwa-san’s range. “Tosei-san asked me to make a smaller zafu cushion, but we do not usually make them,” he recounts. “So instead of a light zafu for zazen, we made a combination of a large zabuton with a small zafu.”

Like their sleep-supporting counterparts, the posture-aiding zabuton and zafu hold deep history intertwined with Zen. The word zabuton comes from za (to sit) and buton (cushion), and its origins trace back to the Edo period, when it was primarily used to support Zazen meditation practices as the popularity of Zen Buddhism rippled through the country. The roots of the zafu go further back to China’s Tang dynasty, where round bulrush-stuffed seats called ‘putuan’ supported meditation.

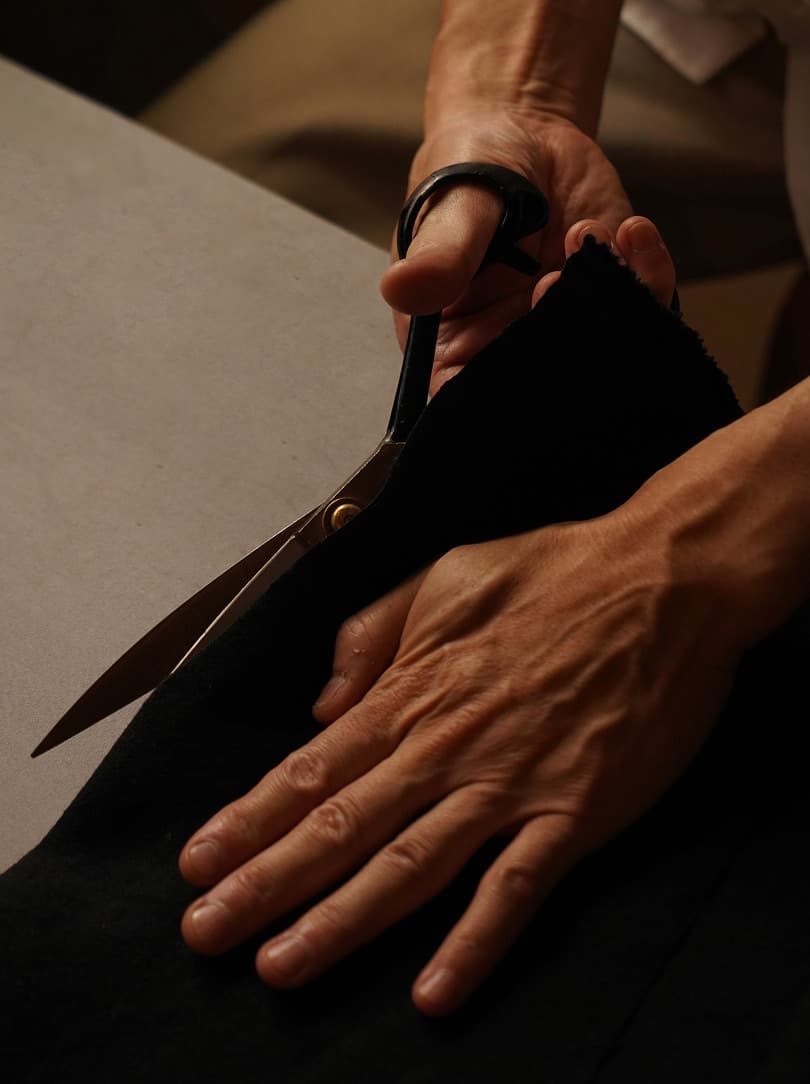

Today, Niwa-san is using the firm cotton blend that we witnessed him blending and pressing to create a zabuton from start to finish – a process that takes him about an hour. With the cotton filling complete, he will now create the square cover from a heavyweight black linen. Back in the showroom, we remove our shoes on the concrete floor and slip through the noren to enter the ground-floor atelier, a compact, milky-lit space, simple and precise.

A Juki sewing machine rests on a mint-green table beside a small right-angled desk. Precisely arranged light grey stacks of cardboard boxes line a wall shelf. Each houses a Gorone Makura, the small, cylindrical cushion filled with buckwheat husks. A wood-veneered floor and MDF-panelled ceiling frame a serene, minimalist environment, complete with a low workbench, an Alvar Aalto stool and a small mobile table. In a matter of minutes, we watch as Niwa-san deftly measures, cuts and sews together the cushion cover, its open side ready to receive the outsized cotton filling.

Cover in hand, Niwa-san leads us upstairs to the loft atelier, where we will witness the most impressive stage of the process – the filling of the zabuton, in which the full capacity of Niwa-san’s finely honed skill reveals itself. Bathed in bright afternoon light, the loft is a living workshop of the futon craft, where large windows open on to a covered balcony. An industrial fan stirs the air, tempering the summer heat that can reach 40 degrees Celsius. Oversized bobbins suspended across a wall form a rainbow of thread, while four spindles of silk – burgundy, navy, black and yellowed cream – unfurl threads from a bulky ceiling beam.

Traditional contraptions are displayed along a high shelf, including a wooden bow and arrow once used to fluff cotton by hand. The back wall holds cotton bales bound with bright yellow string, above which plush kakebuton in pastel green floral casings drape over trestle tables. Several large lint rollers are scattered through the room on standby. On a shelf just below the ceiling, plastic jars contain small cotton buds, grown by Niwa-san’s father in a garden patch tucked into a nearby carpark as a hobby project.

We kneel at the room’s threshold, taking in its intricacies before our attention comes to rest on Niwa-san, who, after a pause, commences a series of intentional gestures. The filling process begins with measuring and weighing the cotton, with each zabuton requiring about 3kg. Niwa-san balances neat stacks improbably high on a small scale.

Once satisfied with the weight, he spreads the sheets across his tatami floor workspace. The movement is unhurried, guided by the wisdom of daily repetition. Then he begins to form the inner cushion. Layers are built in sequence, each cross-laid for balance, and sculpted upwards into a 3D form much larger than the linen zabuton cover that patiently awaits filling. The process recalls the art of origami.

When the stack is half a metre tall, Niwa-san kneels on one side to hold it firm, and rolls it up into a cannoli shape. In one continual movement, he then tucks two sides inward, trapping the air between the fibres and tufting errant bits of cotton to retain an ideal square shape.

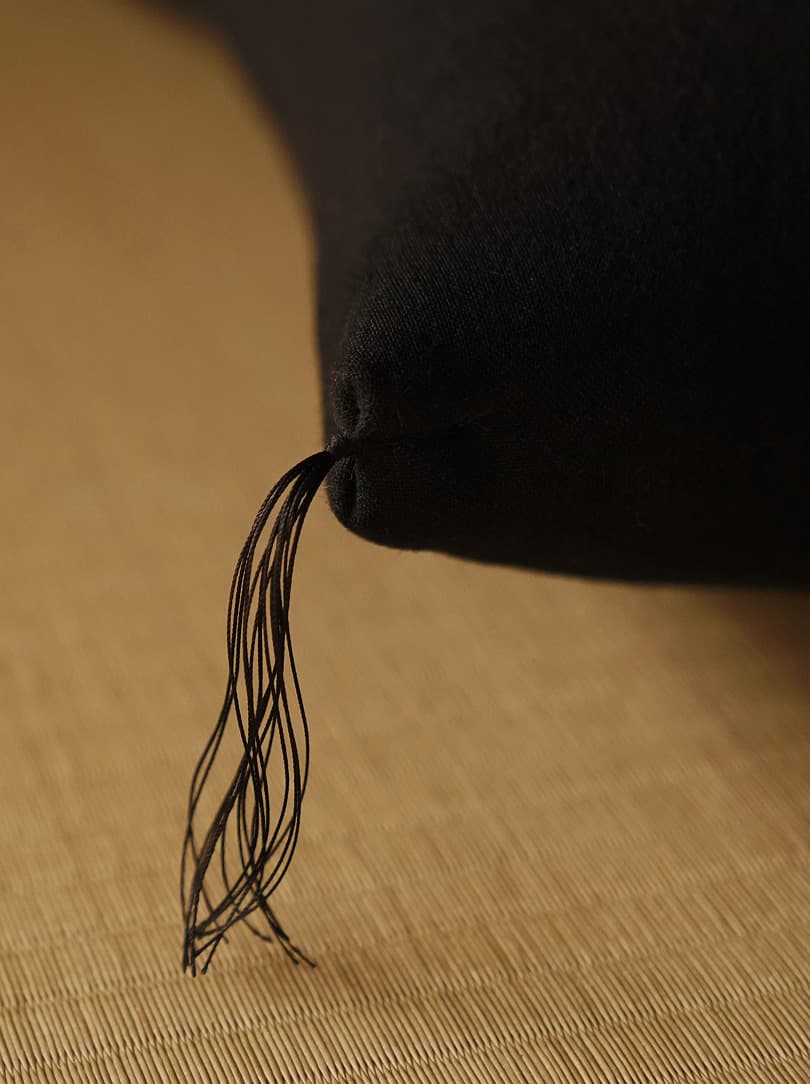

Then comes the masterstroke: Niwa Futon’s signature ‘kado’, or corner, formation technique. Niwa-san crouches over the zabuton, twirling the edges with a gesture that resembles a kabuki flourish, giving way to a firm, upturned corner. We watch, mesmerised, as he repeats the motion for the other three corners – the zabuton’s puffed layers now resembling a perfect four-pointed envelope. A small sheet of plastic eases the fabric inside the cover, turned inside out. Once in, it is folded, turned, thumped and worked meticulously into each corner until the edges are sharp and the surface evenly plush.

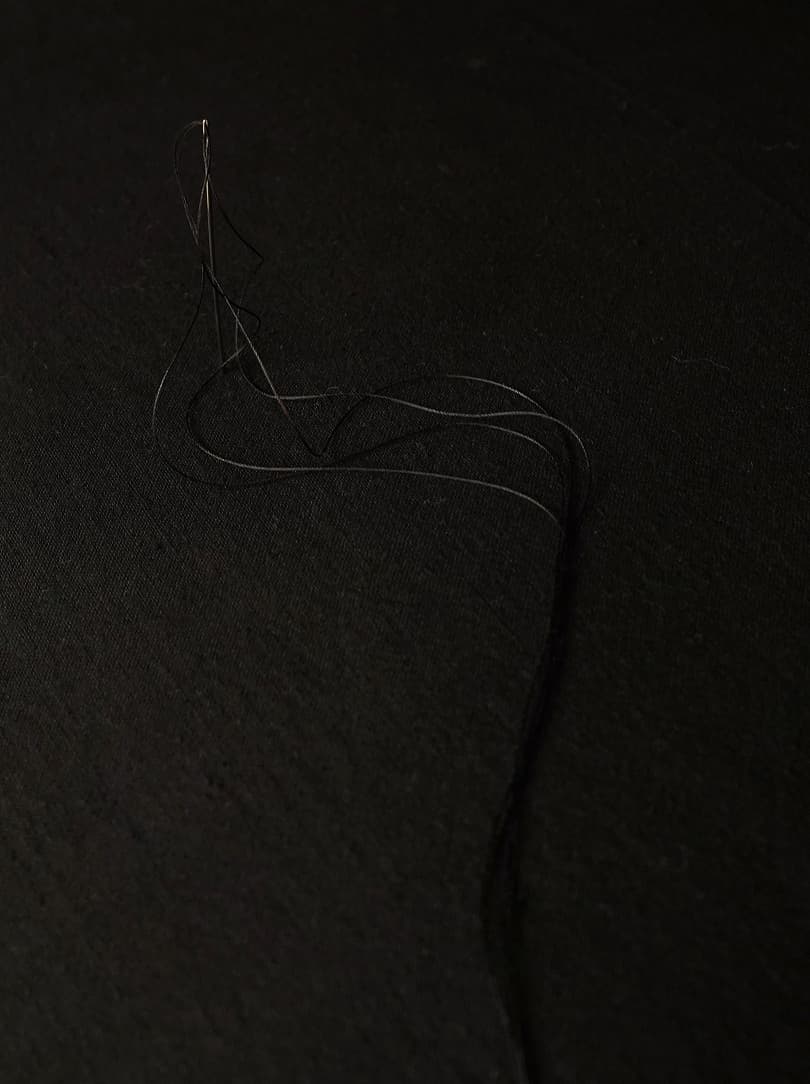

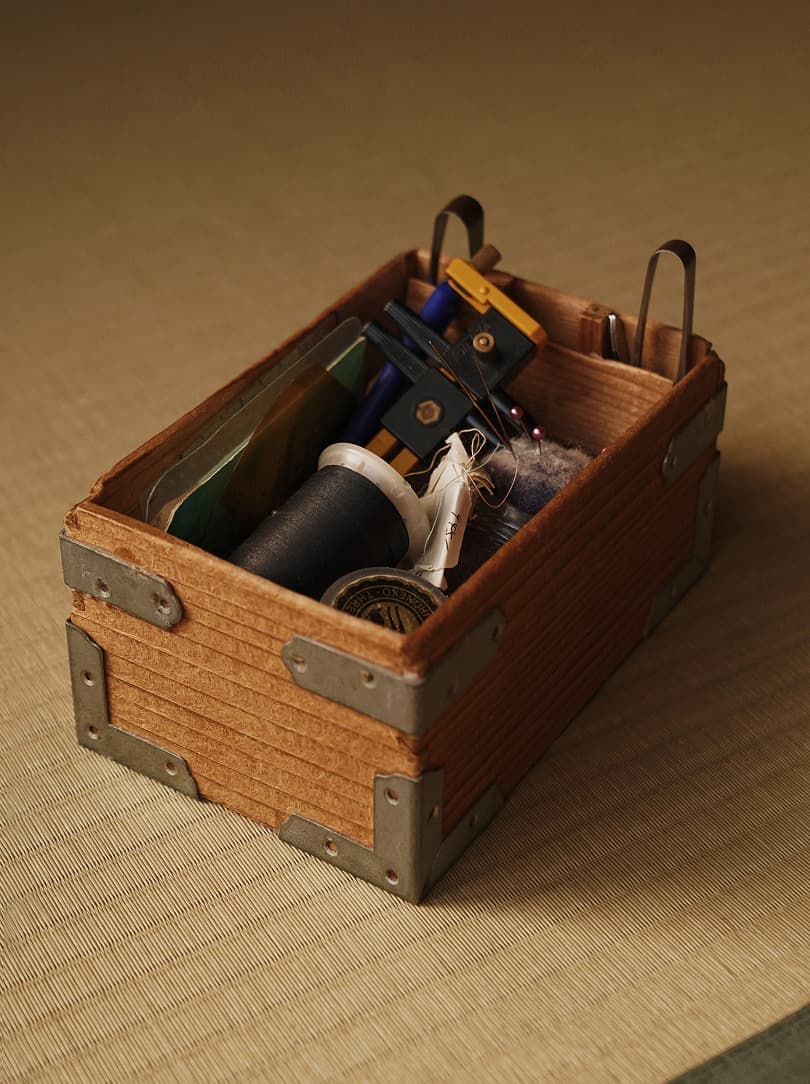

The final stitching, guided through a small wooden box with crosshatch and straight stitches that disappear into the fabric, secures the last edge. Next, the aptly named ‘belly button’ is formed. Silk thread rolls down from the black spools on the ceiling, passing taut through a couple of holes in the centre. The cushion is flipped repeatedly as the thread is pulled through, tightened until a soft dimple is demarcated, then tied into a knot.

A single snip ensures the thread is secure, completing the meticulous finishing that characterises the Niwa signature. In a final flourish, a splay of short threads is secured to each corner, forming neat tassels that accentuate each corner’s precise tip. The final cushion is pleasingly smooth and plump. Each piece is once again stretched, massaged and smoothed until it sits taut, a soft but structured form that emerges as a testament to labour, patience and attention, ready to hold its shape for years of use.

“Through kata, I understand every movement, from the fingers to the feet, as part of my own action. While working, I observe not from my own viewpoint but with objective awareness.”

Observing Niwa-san’s smooth choreography of movements, we reflect on how intensely physical the process is – each movement requiring full mental and physical presence. Accordingly, it feels natural when Niwa-san mentions his practice of karate and kata, the meditative repetition of movement that refines focus and flow.

These disciplines, he explains, make him a better craftsperson: “Through kata, I understand every movement, from the fingers to the feet, as part of my own action. While working, I observe not from my own viewpoint but with objective awareness, always checking how my movements flow.” The acute focus that Niwa-san gives each zabuton, shikibuton and kakebuton that is formed between his hands extends to the care expected from those who use them.

Futons must be aired under the sun every few weeks. The fibres open, moisture leaves and the fabric regains volume. Replacing the cotton every 10 years keeps the piece alive, like changing the soil of a well-tended plant. Across this cycle of use, care and renewal, a Niwa piece ages into familiarity rather than wear.

“I like the word ‘shuhari’. ‘Shu’ means to protect what I learned from my father, and what my family has cultivated over generations. ‘Ha’ means stepping outside what one is doing now, and seeking a new self. And ‘ri’ suggests that by stepping away, you can discover another path.”

In the space where heritage breathes into the present – through unhurried daily gestures of cotton fluffing, folding and edge-forming, Niwa-san sustains the relevance of 150 years of his ancestors’ trade through the dual lenses of duty and passion. He draws on ‘shuhari’, the notion of learning and mastery. “‘Shu’ means to protect what I learned from my father, and what my family has cultivated over generations. ‘Ha’ means stepping outside what one is doing now, and seeking a new self. And ‘ri’ suggests that by stepping away, you can discover another path.”

This guiding principle informs not only the meticulous construction of futons, zabuton and other tools for resting, but also the way they are cherished in daily life. “Our work is to create futons, but I like to see it simply as making things,” Niwa-san says. “By working with many different people, we turn new techniques into different forms. I find this a very enjoyable part of craftsmanship.”

Looking ahead to the question of succession, he reflects on continuity and choice: “I have two children. I do not yet know if they will take over this business,” he says. “Still, I always think that if I work with joy, this craft will surely continue for a long time.”

“I take failures as chances to ask others, to hear and see more, and to think of how it might be improved. By repeating this process over and over, making trial pieces many times, something new finally takes shape. When that happens, I feel joy and want to share it with someone.”

That joy finds ever-evolving expressions – guided not by growth for its own sake, but by creative curiosity. Niwa-san sees his craft as a vehicle for innovation. “By applying futon-making skills I keep discovering new things that can be done,” he adds.

“Even now, I make things like ‘kyousoku’ – an armrest – or tea chests. When making something new, I usually fail at first,” he says of his process. “I take failures as chances to ask others, to hear and see more, and to think of how it might be improved. By repeating this process over and over, making trial pieces many times, something new finally takes shape. When that happens, I feel joy and want to share it with someone.”

As we leave the workshop, bowing in thanks for the joy and skill Niwa-san has shared with us, dusk softens over Nagoya. Small white specks of dust cling to our clothes, and with us goes the zabuton we saw take shape today, presented as a gift. We press it between our hands, solid yet light, sensing the energy exclusive to objects made manually. Its form and feel bear the mark of its maker and the lineage he carries – a living testament to tradition and innovation, linking past, present and the possibilities ahead.