Play Movie

Listen

to Katherine Kennard

reading this story

ENDURING PATTERNS

Bamba Dyeing Factory

The air on the outskirts of Kyoto is thick with humidity as we arrive at the Bamba Dyeing Factory, a fourth-generation workshop specialising in ‘katazome’, the meticulous practice of manual stencil dyeing.

We step inside the printing hall of the low wooden structure, which dates back to the early 20th century. It was built in the style once common to sake breweries and miso warehouses – a single-storey hall of earthen walls and dark timber, its roof beams spanning the full width without a pile foundation or central columns. Recognised by the city for its cultural and architectural value, it stands as a rare survivor of early industrial craftsmanship.

Demarcating the 27-metre-long factory floor, rhythmic rows of wooden printing boards slope gently towards each other, propping up long reams of pale cotton waiting to come to life with colour. Along the walls, screens lean to dry. Pipes and ducts line the ceiling between square vents that release faint gusts of warmth. We inhale the layered scent of damp wood, machine oil and pigment.

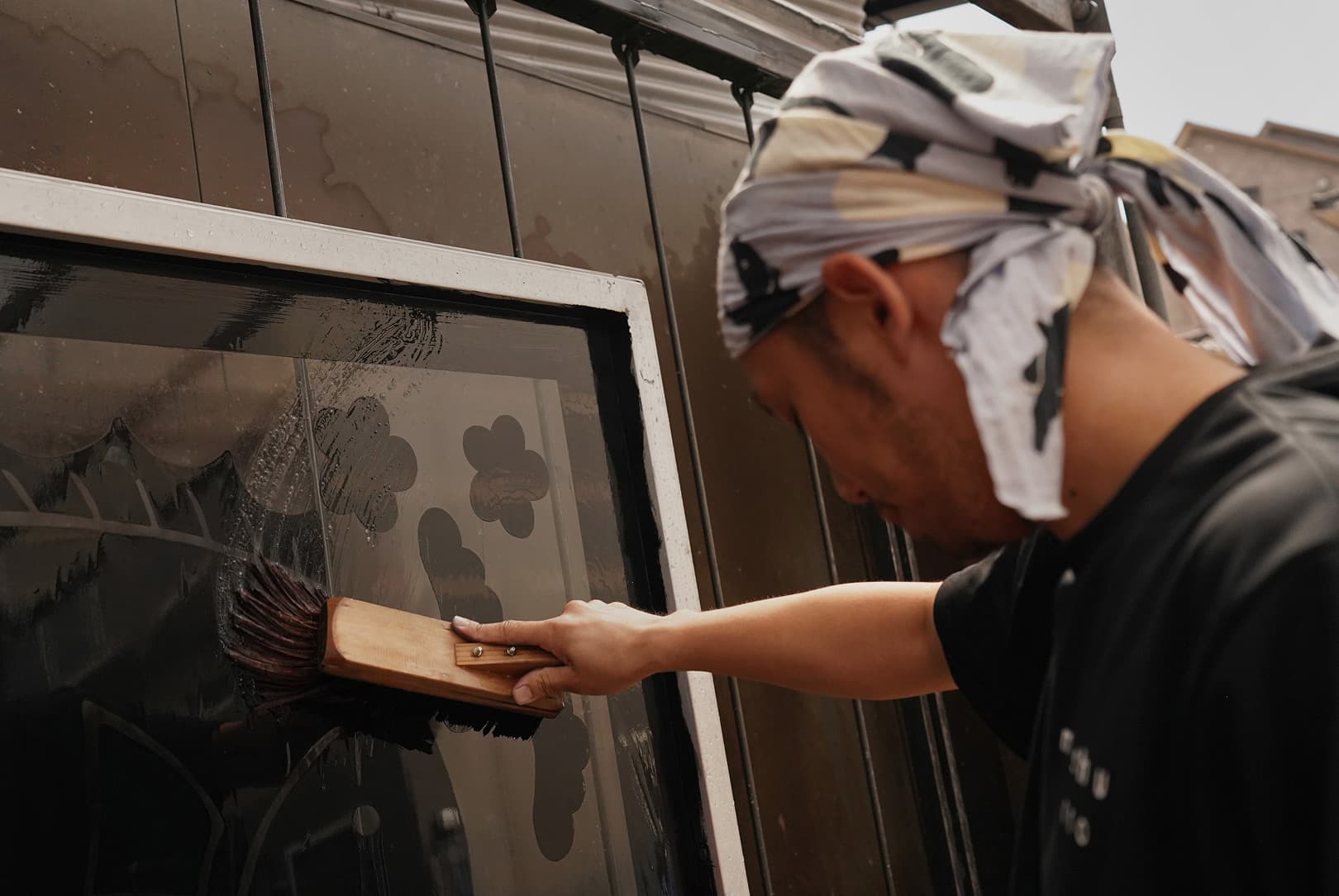

At one of the sloped printing boards, Yoshihisa Bamba moves through a meticulous choreography of ‘nassen’ – hand-printing – as though in a trance. His tanned, sinewy frame belie his eight decades. A deep blue T-shirt is tucked neatly into tailored trousers; wire-framed glasses catch the light. The palms of his hands bear the pink residue of a crimson dye just mixed. He aligns a silkscreen and lifts a large horizontal ‘skeji’, or squeegee, drawing ochre yellow up and down the fabric in measured strokes. The pigment settles into a dense sheen as he lifts the stencil and sets it precisely onto the next section, advancing methodically along the full length of the factory floor.

We observe as Bamba-san Senior rhythmically applies a series of five stencils – one for each colour and shape – along the entire fabric ream. The design gradually takes form: a procession of cats stretching across the board, each rendered in soft black, grey and white, with pink-tipped paws and bright, alert eyes. Their fur, outlined in loose, expressive lines, ripples as if caught in motion.

Norio Bamba, his son and the company president, explains the intricacies of this highly technical process. With an open demeanour, a kind smile and focused pragmatism, he moves deftly round the space wearing a white cap, grey T-shirt, khaki cargo shorts and rubber clogs. He gestures to a row of freshly dyed fabric. “We call it ‘tenchi-nuri’ – top-and-bottom dyeing. When stretched across the boards, the top faces forwards. The pattern moves towards the top. The lower edge becomes the foot.

“One piece is easy enough. With a little practice, anyone can manage that. The real challenge is maintaining the same pressure for 1,000 metres.”

NORIO BAMBA

“Ideally, the pressure should be uniform – top, bottom, left and right. The goal is evenness,” he says of the skill involved. But in practice, the right hand often presses harder than the left. More pressure tends to go downwards, less upwards. One piece is easy enough. With a little practice, anyone can manage that. But 50 or 100 metres – even 300 metres of consistent work – that’s where the real difficulty lies. The real challenge is maintaining the same pressure for 1,000 metres.”

The discipline this work demands traces a long lineage – back to 1913, when Bamba Dyeing Factory was founded by Zenzo Bamba in Fushimi, Kyoto. This was during the Taishō era, a brief interlude of peace and optimism between the upheavals of Meiji industrialisation and the Second World War. It began as a kimono dyeing workshop, working with Tango chirimen silk at the standard fabric width of the time, which was 38 centimetres. Kyoto’s textile trade was flourishing, and the city’s dye houses supplied their colourful silks to department stores in Tokyo – the ultimate mark of prestige.

The business began through Japan’s traditional apprenticeship system, a structure linking rural families to urban craft through rigorous, lifelong training. “Apprenticeships came from poor farming families,” Bamba-san explains. “Families would send their children to companies in the city. The company that took them in didn’t just make them work. For those who proved capable, the company would give them their own factory through a noren-wake [branch licence]. Those former apprentices then went independent and ran their own businesses.” One of them was Zenzo Bamba, who, through this system, gained his independence and went on to build a legacy that would reroute the fate of his descendants.

After the war, demand for kimono declined, and many hand-printing factories turned to machine production. Bamba did not. That decision proved crucial to the factory’s survival and success. Rather than pursuing scale, the factory continued to refine its approach over time, moving from silk to cotton as the main material and deepening the precision of its handcraft. Techniques once used for narrow kimono fabrics were adapted for wider widths – 70 and 90 centimetres – suited to ‘furoshiki’, traditional wrapping cloths, and ‘tenugui’, versatile hand towels used for wrapping, cleaning or display.

Furoshiki, Bamba-san explains, were originally used as cloths spread beside the bath – ‘furo’ meaning bath, ‘shiki’ meaning laying out – to hold clothing before washing. “Nowadays, they’re used as an inner bag, and increasingly for packaging,” he notes, adding that demand is rising.

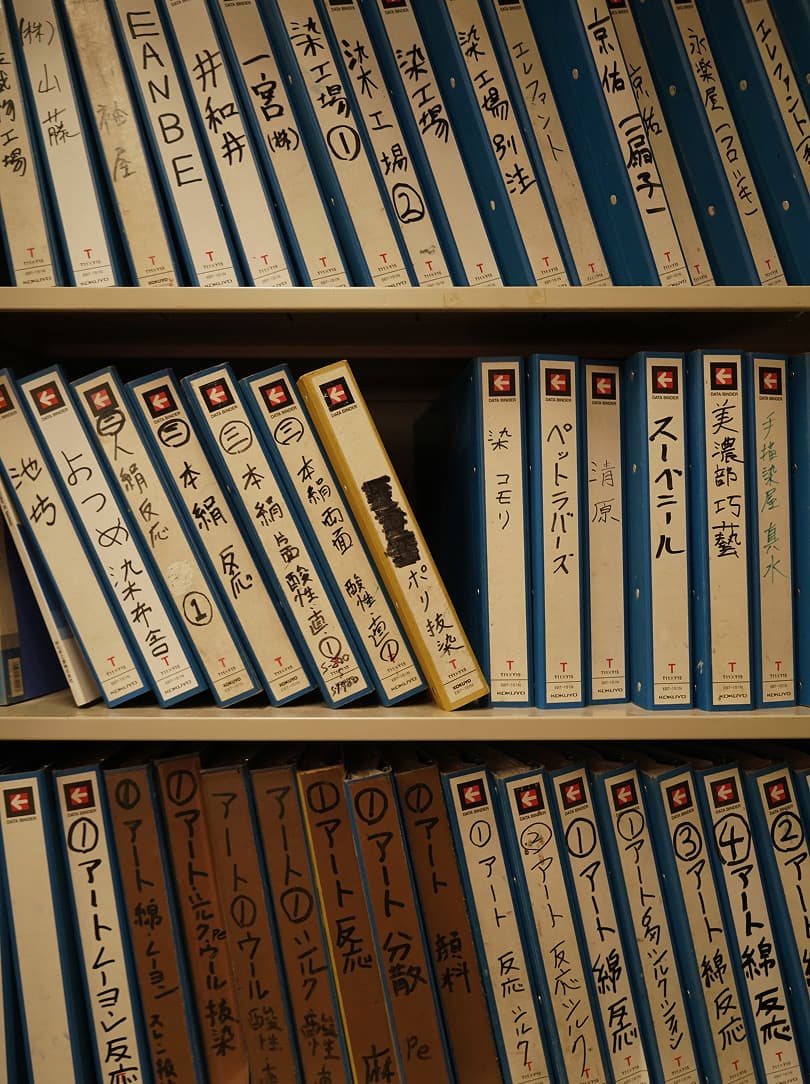

Once, every pattern was made to order for individual clients; today, about 60 original designs are also produced in-house, many first conceived by Kyoto kimono shop owners. The factory holds an archive of more than 2,000 stencils, stored in the open air beside the main hall.

Each furoshiki can carry up to 30 colours, though most feature far simpler combinations. Because furoshiki tend to be used as inner wrappings rather than displayed externally, their motifs can be as vivid or playful as desired. As Bamba-san remarks, “even if the pattern is flashy, it doesn’t matter.”

“Our motifs never repeat. Top and bottom don’t connect, nor left and right. No combination aligns. That stops replication.”

He pauses, as his father lifts the squeegee from the final section of fabric and sets the stencil aside for washing. The replicability of a furoshiki design, he says, is what separates mass production from authentic craft. “Repeated patterns can be copied endlessly. Make one tile, and the machine prints it infinitely. It just repeats in all directions. Once one unit exists, it fits like a puzzle,” he says impassionedly. “It becomes scalable. Machines handle it with ease. But our motifs never repeat. Top and bottom don’t connect, nor left and right. No combination aligns. That stops replication.”

He points to the outer edge, where the colour runs right to the border. In Japan, the ‘mimi’ – the selvedge, or self-finished edge – is dyed completely by hand, a hallmark of true artisanship. The precision this technique demands is absolute; any flaw would be immediately visible.

Unlike European cloths, which are hemmed on all sides, furoshiki are stitched only at the top and bottom. The sides are left raw, finished by the loom itself. Bamba uses only fabric stitched at the top and bottom, leaving the selvedges unstitched so that the dye can run edge to edge. This method, carried through from kimono production, is part of what defines a furoshiki. Hem all four sides, and it becomes something else entirely.

Dyeing the selvedge is notoriously difficult. The woven edge creates unevenness that machines cannot manage, so it must be done by hand. Many factories avoid it, preferring to cut from wide bolts for efficiency, but the Bambas have kept this custom alive. “To be able to say, ‘we dye the selvedge’ defines a place like this,” Bamba-san tells us. “We take pride in that detail.”

The hand-dyeing step we have just witnessed – known as nassen – is the third in the Bamba method. Bamba-san gestures for us to follow him into the modest, MDF-clad office adjoining the hall, to demonstrate the first: the creation of colour. The change in atmosphere is instant. The compact space smells faintly of glue and warm timber. Shelves hold tubs of pigment powder, folders of accounts and stacks of drawings smudged with primary colours. On one chestnut-toned wall hangs a single Noh mask, carved by Bamba-san Senior – the last remaining of several he once made. He studies their subtle differences the way he studies colour.

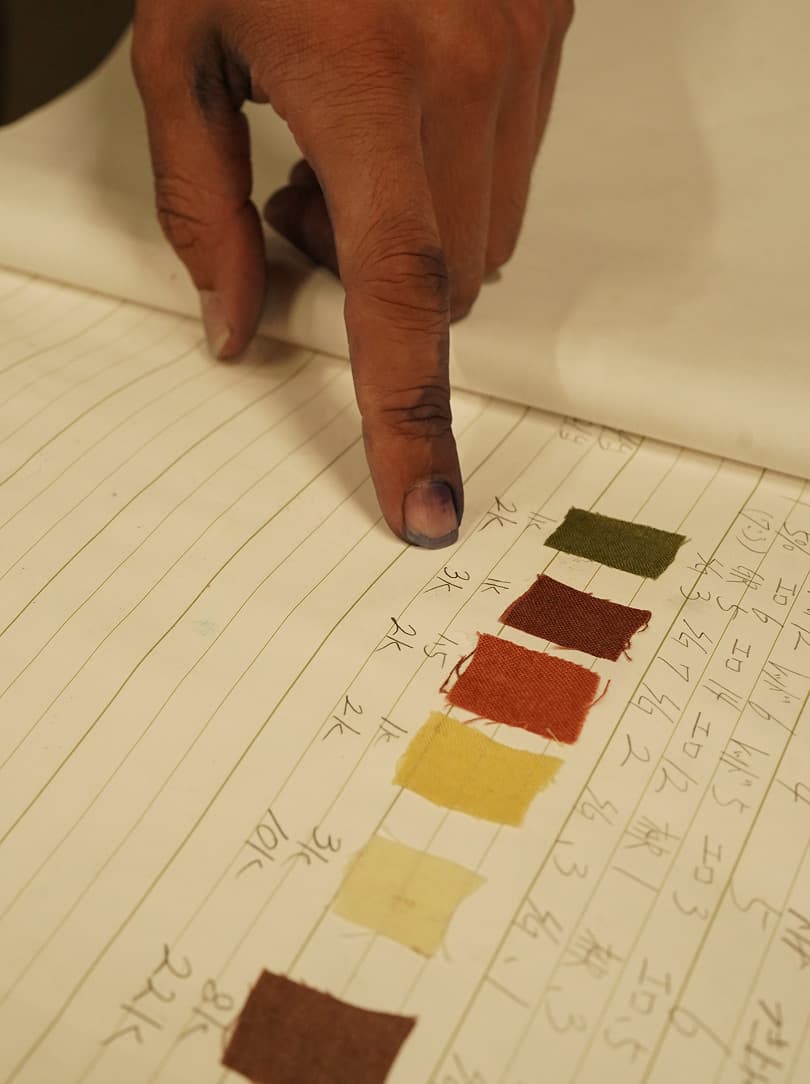

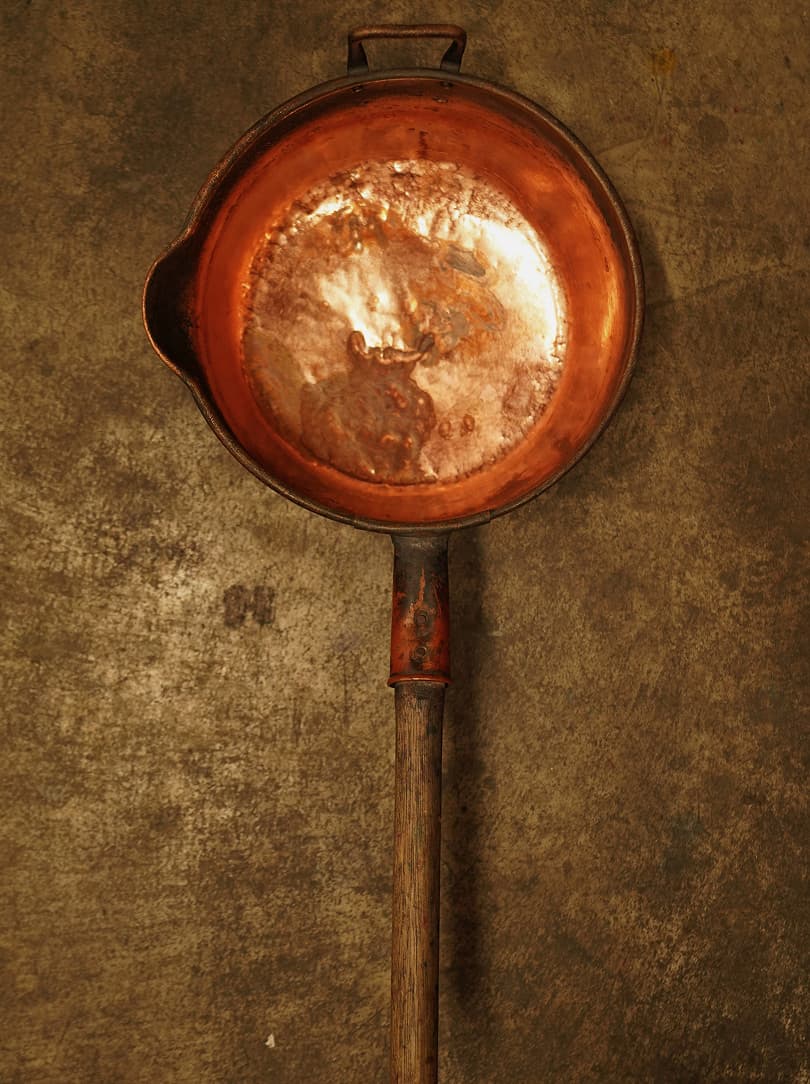

Round, sky-blue buckets marked with red kanji line the concrete floor, each filled with glue or pigment paste in shades of crimson, sapphire and emerald, their viscous surfaces gleaming. Here, the dyes we have seen printed in the factory take shape. Pigments are blended with rice-bran paste in precise ratios – 1 kilogram of glue to 60 grams of pigment – creating a smooth, heavy medium.

Streaks of white silicone in each bucket keep the dye cohesive and dense. The colours appear solid, yet this brilliance is only temporary. The pigment still sits on the surface, waiting for heat and humidity to draw it deep into the fibres – a process that will unfold the next day, in a separate steaming and washing plant across the city.

“The future of a business often hinges on the moment when generations change. Those who handle it well endure.”

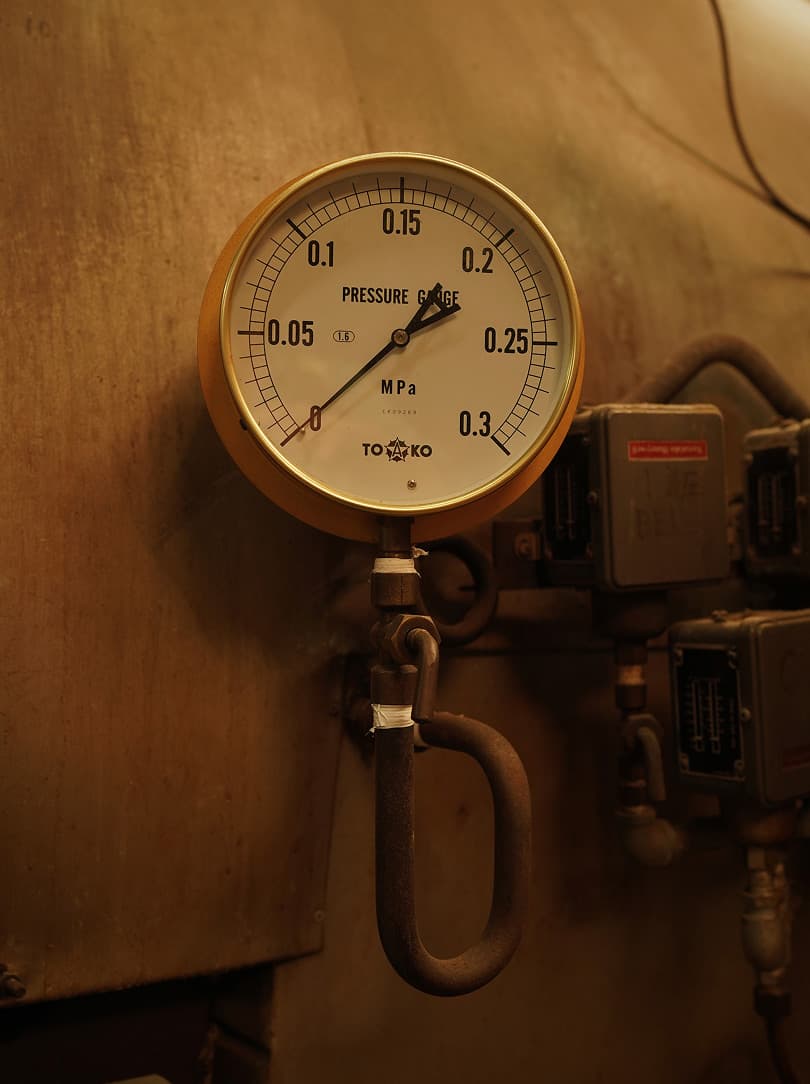

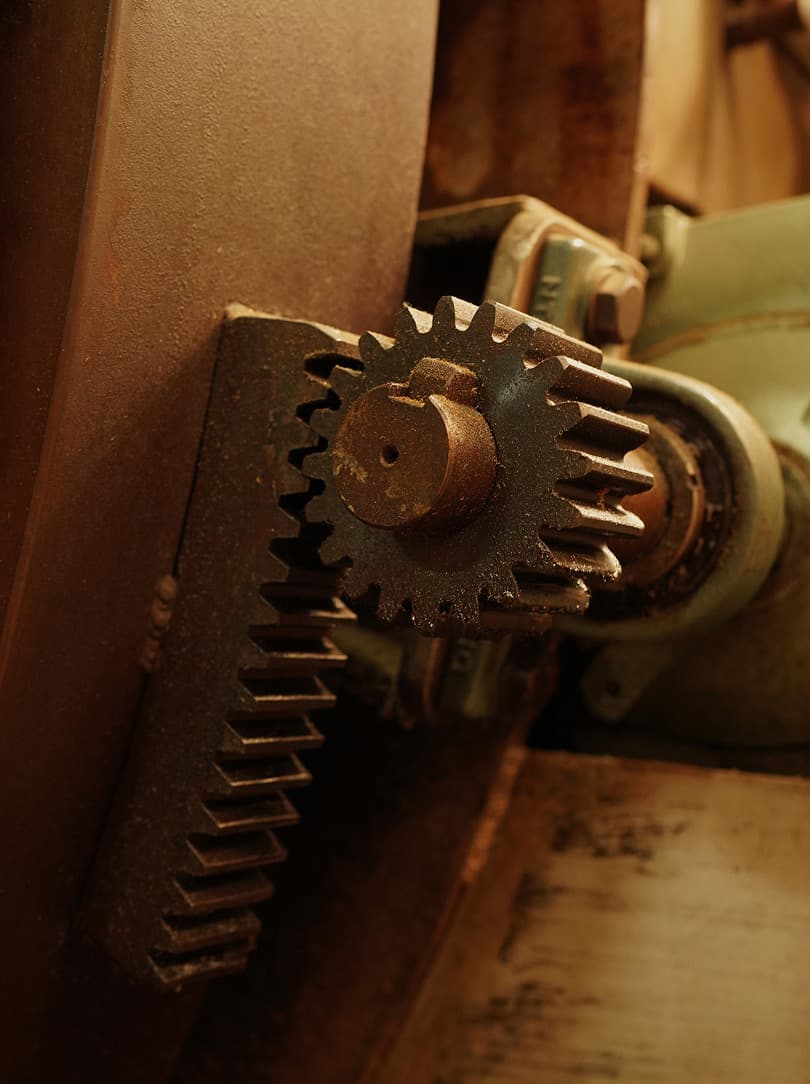

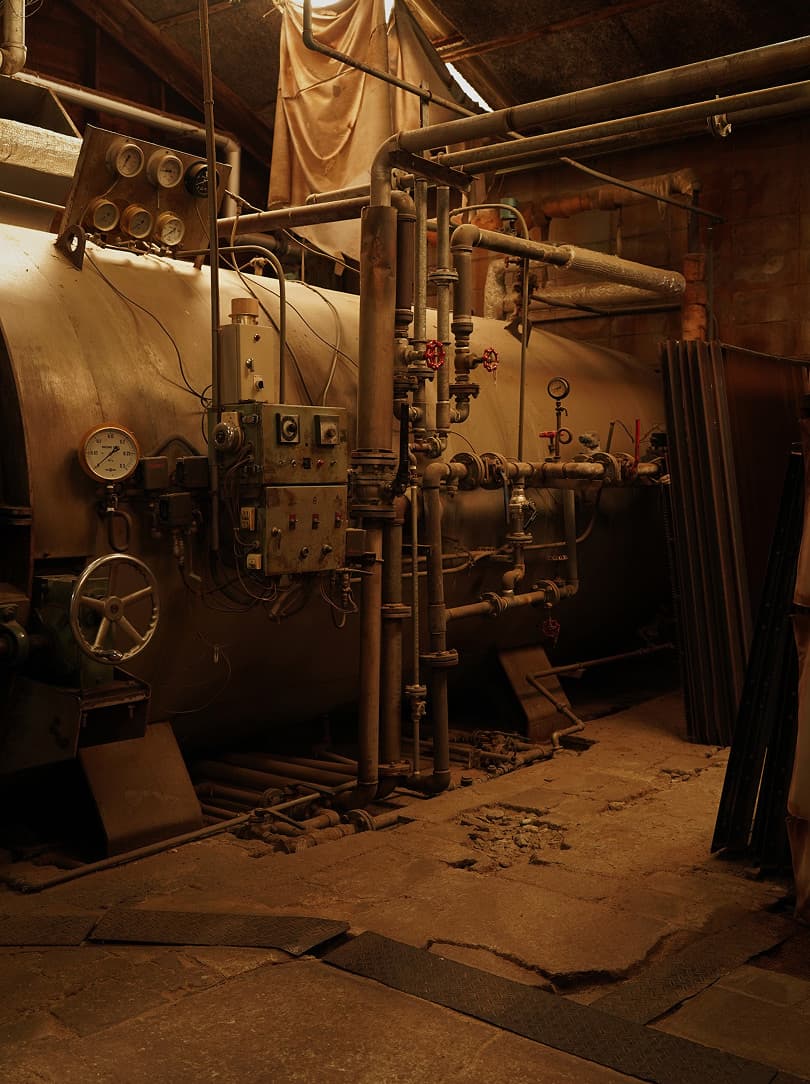

The following morning, we set out to Kyoto’s southern industrial quarter to see the cavernous workshop for ourselves, set among a tangle of low workshops in narrow lanes that hum with the murmur of small-scale production. Sunlight filters through corrugated panels, turning the haze of steam into a soft mist. The air swells with heat and a drift of chemicals. Everything hums and hisses: water rushing through pipes, fabric gliding over pulleys, valves clicking open steadily.

The facility is divided into two soaring levels – downstairs, where the initial steaming and washing takes place, and upstairs, an enormous loft dedicated to the final steaming and drying stages. We take in the sweltering industrial bathhouse atmosphere, bathed in a golden light. Yellow pipes run along the beams, patched with silver tape, while thick ducts twist overhead. Beneath them, a tangle of valves and cables traces the path of the machines.

Cylindrical steamers, their metal drums patinated to shades of bronze and pewter, line the back wall like small train carriages. Here, the first stage begins: long rolls of cloth are fed into the steamers, which are the size of small carriages, where heat and humidity draw the dye deep into the fibres. We watch steam pump out of their vents, feeling our temperature rise with it.

Once removed in neat bundles from the great steam vats, the now colour-fast fabric is manually drawn along a 10-metre washing basin, long and low, its steel surface clouded with mineral deposits that gleam faintly under the fluorescent light. Glue and residue dissolve into the bubbling cloudy water as each length is rinsed and cleared.

Freshly washed, the fabric is bundled neatly and attached to a vertical rail that hoists it up to the loft above. There, the next round of steaming – known as ‘yunoshi’ – restores the fabric’s original width and smooths away any remaining creases. The upper level stretches open like an attic, lined with pipes and ducts that breathe out waves of warm air.

Swathes of cloth loop across the rafters, suspended on bamboo poles that form a giant washing line, 15 metres high. As they lift and fall, the cotton dries within minutes, moving with the steady rhythm of a slow tide. When the cycle is complete, the fabric will be cut and hemmed – on two edges only, as custom dictates – ready to return across the city as finished furoshiki, its patterns now permanent.

“I saw the business could easily collapse, so I shifted direction. The first goal was […] to move from craft to true industry. We wanted to be needed as an industrial company, not just an artisanal one.”

Later that afternoon, we come full circle at the Bamba headquarters. Here, the complete range is displayed in a modern showroom newly added to the original factory and office, designed to host visitors for wrapping demonstrations and workshops. One of its light timber walls is covered, floor to ceiling, with furoshiki displayed on wooden rungs, creating a vivid patchwork of pattern and colour.

Featuring the factory’s own designs, the fabrics span saturated primaries and muted neutrals. Some take shape through geometry – spirals, lattices, sharp triangles – while others show a freer hand: red birds on yellow branches, white gourds scattered across coral and navy, clusters of camellias.

Bamba-san is contemplative as he speaks about the company’s passage through time. “The future of a business often hinges on the moment when generations change – that’s when most falter,” he says. “When Zenzo passed it to the second generation, then from the second to the third, and the third to the fourth, those were the most critical points – whether to close or continue. Those who handle it well endure.”

When Bamba-san himself succeeded the family business, he realised how fragile even a long-established workshop could be. “I saw it could easily collapse,” he recalls. “So I shifted direction. The first goal was to find entirely new customers beyond the ones we had – and to break away from traditional industry. To move from craft to true industry. We wanted to be needed as an industrial company, not just an artisanal one.”

The change coincided fortuitously with what Bamba-san calls Japan’s ‘craftsmanship boom’ – a renewed public interest in how, and by whom, things were made. “There came a time when vegetables were sold with photos of the farmers on them,” he explains. “Until then, people trusted the shop, not the producer. But then many began preferring to buy directly from the makers. That was the start.”

At that moment, the Bamba factory had no inkjet printers or transfer machines, only the same hand-printing set-up that had carried it through generations. “Perhaps the second or third generation simply chose to keep doing hand-printing,” he says. “Maybe they avoided investment because it was burdensome. It survived by chance – but that chance proved valuable.”

As the craft movement gained momentum, even department store staff were expected to understand the process behind what they sold. “Before that, no one ever visited our factory,” Bamba-san says. “Then store buyers started coming for study visits – they wanted to see how everything was made. At first, there were only a few visits a year, then a few each month. And the final push came from social media. Suddenly, anyone could share images instantly. We had to show the factory visually – that became our approach.”

The visibility attracted attention from abroad, including renowned luxury fashion houses. “When European brands come here, they always say the same thing: what counts is where, by whom, and how it’s made. The story matters more than the pattern. If it’s made in a 100-year-old wooden workshop in Kyoto, by hand, that story carries weight.”

He pauses, smoothing a furoshiki beneath his weathered hands. “Being the one they request by name – that stems from manual craft, from the methods we’ve kept for generations. Yet if it becomes pure ‘traditional craft’, a museum piece, it stops working commercially. It must remain capable of production. Our old method happens to balance craft and scale perfectly.”

That international recognition has, in turn, rekindled local appreciation. “A small brand like ours being given a full month each year at [leading Tokyo department store] Matsuya Ginza – that’s unheard of,” Bamba-san says. “It’s the most exclusive exhibition space in Japan, and they give us the front windows. It’s not thanks to us individually, but to the generations who came before. That legacy gives us strength.”

“Being the one brands request by name – that stems from manual craft, from the methods we’ve kept for generations. Yet if it becomes pure ‘traditional craft’, a museum piece, it stops working commercially. Our old method happens to balance craft and scale perfectly.”

The fact that Bamba Dyeing Factory still operates in its original wooden form, practising hand-printing rather than mechanised production, is, as Bamba-san admits, “thanks to luck”. The family made decisions at the time that seemed risky, even unreasonable. “Had we moved away from hand-dyeing, and switched fully to machines, this place would probably be an apartment block now,” his voice carrying a tangible note of poignancy.

“When I took over the company, the proposal was to demolish the entire factory. People calculated the taxes and costs – ‘Tear it down,’ they said, ‘turn it into apartments or garages.’ Keep only the name, become a property company. But this factory had survived countless typhoons and even the Great Hanshin Earthquake. Would you really destroy something that’s stood through all that? So we kept it.”

That choice to remain as they were proved decisive. “Other factories invested in machinery, but we didn’t, and so this place has remained as it was,” he reflects. “Longevity naturally creates know-how. The technical details – like dyeing the mimi – make it difficult to replicate, so the work stays. After decades in dyeing, it’s hard for others to take that work away. That might be the secret to lasting as long as we have.”

It took firm resolve to resist the constant pressure to modernise. Offers came often: subsidies for inkjet or transfer printers, full paperwork prepared by the manufacturers themselves. “They came with the pitch: ‘This old way won’t survive’,” Bamba-san recalls. “But hand-printing on slanted boards like this – that’s uniquely Japanese. Inkjet can be done anywhere, but this can’t be replicated. It was fortunate we didn’t demolish this building or bring in those machines. That luck kept us here.”

“Inkjet can be done anywhere, but this can’t be replicated. It was fortunate we didn’t demolish this building or bring in machines. That luck kept us here.”

As we unfold a furoshiki in our hands, feeling the cool cotton and the smooth, perfectly dyed edges between our fingertips, we reflect on how this business has endured. Its strength and give between craft and commerce mirror the wooden factory that shelters it. During a typhoon 76 years ago, Bamba-san tells us, half the structure was destroyed and rebuilt using interlocking joinery and heavy ‘kawara’ roof tiles that anchor it in place. Its earthen walls still show traces of weathering, and the columns lean ever so slightly from storms past. Built to flex rather than resist, it swayed through the Kobe earthquake of 1995 without a single tool displaced.

In the same way, Bamba Dyeing Factory has withstood the shifting natural and market forces around it – held firm by instinct, adaptability and a fair amount of luck. From the fine silks once used for kimono to the modest cotton cloths now made for wrapping and carrying – often seen only by their users – the factory’s focus has shifted with time. But the resolve of those guiding it has never wavered. Its endurance feels as remarkable as the wooden hall itself: steadfast after more than a century of change.