Play Movie

Listen

to Katherine Kennard

reading this story

WOMEN OF THE SEA

Ago-wan’s Ama Divers

By late morning, the waters of Ago-wan carry a gossamer sheen, their surface brightening as the day rises. Light settles across each inlet, and the air holds salt, resin, and a faint sweetness released as the pine forests warm beside the sea. The water appears almost weightless. Cobalt gathers in the deeper pockets, jade drifts near the rocks and silver touches the tide’s edge. We crouch at the shoreline and dip our hand in; the coolness feels fresh. As the water recedes, it traces a pale gleam across the rocks and releases a touch of iodine that lifts into the heat.

Ago-wan translates to Ago Bay in English, and is the place that inspired our name. It lies within Ise-Shima in Mie Prefecture on Honshu, Japan, a coastal region known for its history of ‘Ama’ diving. Ama, literally ‘women of the sea’, practise a traditional form of freediving that once sustained entire communities. The coastline of the Shima Peninsula, together with Toba at the mouth of Ise Bay, has continued these practices for generations. Today, the Ama usually dive further out in the open ocean, rather than right within Ago-wan as they have done in the past purely for pearl cultivation.

The tradition itself reaches back many centuries, with written records appearing as early as the 8th century ‘Man’yōshū’ – Japan’s oldest surviving collection of poetry, which describes female divers harvesting seaweed and shellfish from the seabed. Their work emerged from the geography of the archipelago. The sea offered food, and those living along the coast grew skilled in descending through clear water with nothing but breath, instinct and familiarity with the tides. Early Ama often entered the sea wearing little more than white cloth – garments tied to beliefs of purity and protection.

Pearl cultivation later added another strand to this history. In 1893 Kokichi Mikimoto, the son of a noodle shop owner, invented methods for producing cultured pearls in these waters. As the technique spread among cultivators, Ama divers became essential, lifting oysters from the seabed so the nucleus could be implanted and the process refined.

Each oyster had to be collected by hand, taken ashore for nucleation, then returned with equal care to underwater areas sheltered from storms, red tide and drifting predators. Divers worked from wooden barrels used as floating platforms – a spot to place their catch, including pearl oysters, to rest between dives and store tools. During the early Shōwa era, this practice expanded. Their effort sustained an industry that played a strong part in Japan’s presence on the world stage. And while this coastline was the inspiration for our own name, it’s the skills of the Ama that stand for our vision: finding, celebrating and creating ‘the pearls of this world’ – whether they come in the form of a single handmade product, an unforgettable experience or a place to feel at home.

“When we go out to sea, Aonomine Mountain is a landmark. From the water, it guides us.”

KAORI ARAI

We have come to Ago-wan to witness the present-day continuation of a tradition carried through countless tides. Before we follow our Ama hosts out onto the water, we drive inland to meet them at a local temple, leaving the brightness of the bay for the shaded roads that climb Aonomine Mountain. The air cools as the track winds upward beneath tall evergreens and a broad-leafed canopy, each turn drawing us further under their cover.

The gate of Shōfuku-ji appears between the branches as we round a bend, its tiled roof set close against the slope. It marks the approach to a place of deep significance for the Ama of this region. They come here before the diving season to seek blessings, set intentions and later return in thanks once their work in the water is complete.

We step out and make our way through the gate. A faint scent of earth and moss rises from the ground, and the forest draws close at once. Insects hum through the trees; water murmurs somewhere deeper within. The path underfoot shifts from gravel to cracked stone, softened by patches of green. Bronze lanterns stand along the walkway, their surfaces dulled by weather into muted shades of grey-green.

Down the path, a small stone well waits to one side. Here, we pause, wash our hands and lift a little water to our faces with a worn ladle – a gesture of purification that prepares us for the crossing into sacred space. Coolness settles on our skin as the forest thickens around us.

Shōfuku-ji traces its beginnings to the early 9th century, and age marks every structure. The oldest shrine bears nearly four centuries of wear; the wood along its beams has faded to the pale silver you see only after long seasons of sun, rain and salt carried up on the mountain air. Carvings beneath the eaves hold fine detail: curling leaves, cloud motifs, small creatures hidden in the grain. Nearby, a long veranda stretches along the hillside, its balustrades softened by touch and time.

A figure emerges through a door in the vast entrance hall, bowing deeply to welcome us into the temple, then gestures for us to follow. Removing our shoes, we learn she is the head priest, a role passed on to her after her husband, the former head priest, died. She leads us into an entry space beneath a richly carved ceiling. Waves and drifting clouds are worked into the beams, the wood with a soft sheen that traces years of salt-brushed mountain air. Along the upper beams, paper talismans and framed photographs – of fishing vessels dressed with flags and streamers – turn the hall into an album of the maritime lives that return here season after season.

“Ever since I first saw Ama diving at 19, I thought it was wonderful and had wanted to try it myself one day.”

Further inside, the atmosphere dims. Silent rooms are floored with dark boards and edged with red carpet worn smooth by years of footfall. The main hall opens with a sudden richness. Gold catches light in small, bright points: filigreed canopies suspended from the ceiling, tasselled ornaments that sway almost imperceptibly, dragons carved at the corners with their jaws set round rings of metal.

Tall red hangings fall in long folds from the beams, their patina patterned with faint creases that show how often they have been lifted and lowered. Beneath the canopy, lacquered tables carry ritual instruments, each inset with small arcs of gold. Bronze incense burners stand with rounded shoulders, darkened to a deep green. Sheets of sutras rest on angled stands, their pages flecked with ink strokes that catch the glow of nearby candles.

A low fire burns in a sunken hearth at one corner, sending a warm pulse through the hall. Incense rises in thin vertical threads, drifting past drums with taut, pale skins and stools stitched in patterned cloth. Around the altar, objects accumulate: drums, bottles, gilded finials, red cushions, folded scripts. Each element seems to carry a specific role in the cycle of blessings for protection at sea and abundance in the work ahead.

Here, we encounter Ama diver Kaori Arai. In her early forties, with long dark hair and a scattering of freckles across her cheeks, she exudes a composed presence. Her hands rest gently in front of her, shoulders relaxed, as she waits for the ceremony to unfold.

A monk enters in layered robes of deep plum and tangerine. He kneels by the hearth, lifts a string of beads, and begins to chant in deep, resonant tones. The sound moves through the room in a continuous line. A bell marks the rhythm. He flicks water over the embers, which answer with a brief crackle and a brighter tongue of flame. Smoke, incense, and the faint smell of charred wood mingle under the high ceiling.

Arai-san kneels and draws the warmth of the fire towards her face with slow, measured gestures. The glow illuminates her features and picks up the curve of her cheekbones, the line of her nose, the calm set of her mouth. In that moment, the distance between mountain and bay feels small – the same breath that will sustain her underwater now filling her chest in the presence of fire and chant.

When the ceremony reaches its close, she steps forward, bowing deeply to signal her gratitude. The monk prepares a small wrapped bundle, the ritual objects used in the rite, and places it in her hands. She receives it with a slight bow, holding it close for a moment before rising.

“I started questioning a society that produces and discards so much, and I no longer wanted to be part of that cycle.”

Outside again, the red of a curved bridge cuts through the green, the carved beams above the entrance carry their salt-softened patterns, and the forest settles around the buildings. We pause at the threshold of the temple as Arai-san turns toward us with easy warmth and reintroduces herself with a bow, signalling the shift from sacred ground back to the world below.

As we meander back towards the temple gate, she tells us how she arrived in this work. Born in the Mishima District of Osaka Prefecture, she entered the Ama world at age 30. The path towards diving began much earlier, when she first witnessed Ama at work on Awaji Island at just 19. She had known the profession existed, but seeing it first-hand left a lasting impression. “Ever since then, I thought it was wonderful and had wanted to try it myself one day,” she says, a nostalgic smile drawing across her face.

Before her path led her here, Arai-san’s life belonged to a different pace. She worked in Osaka at a large department store for household goods. Although her role within the company expanded, the churn of sales and consumption began to sit uneasily with her. “I began to feel I couldn’t stay in that kind of environment, given that it was a job built on selling large volumes to many customers,” she tells us. “I started questioning a society that produces and discards so much, and I no longer wanted to be part of that cycle.” Her decision to leave opened the path that eventually led her here – to the sea, and to the daily routines of Ama life.

“When we go out to sea, this mountain is a landmark,” she shares, gesturing to the deep green around us. “From the water, it guides us. There is a legend that Kannon arrived riding a whale, and with that story the mountain draws prayers for safety at sea and good catches, and the temple receives that faith.”

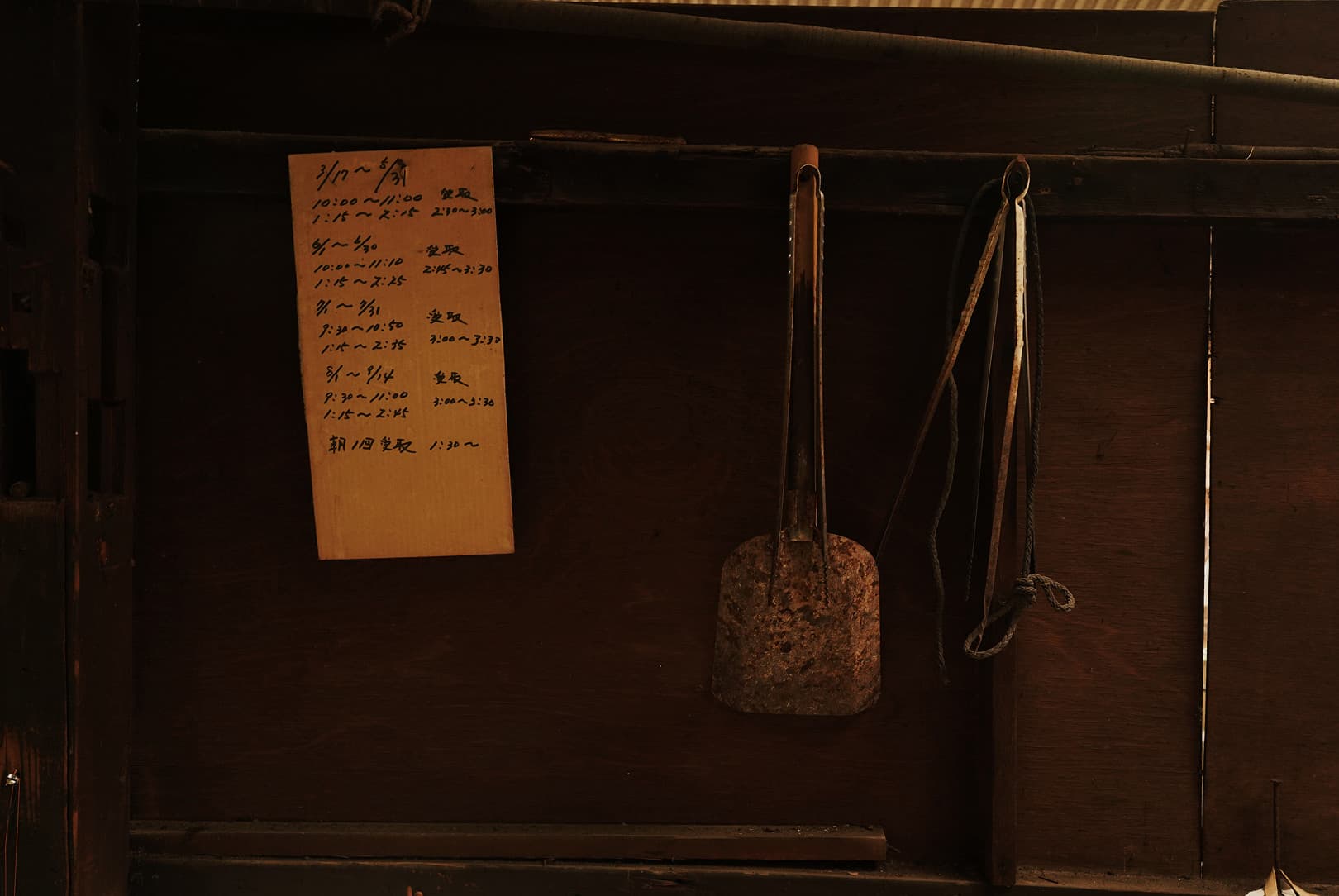

Her Ama community of Shijima marks its year through three visits to Aonomine. The first falls on 18 March, ahead of the 1 May season opening, known as ‘kuchiake’, when divers meet to set the rules for the year and perform ‘ishigyō’ – a rite in which the Heart Sutra is written on a stone and placed in the sea at Shijima. The second visit takes place in late June, a mid-season pause once known as ‘nōagari’, when those who worked both sea and fields stepped back from labour to pray. It’s also related to the arrival of sharks at this time, around the end of the rainy season, when they swim close to the shore and a short break from diving is taken as a precaution – it’s widely believed that even the sight of a shark could bring death to a person. The final visit is in mid-September, after the divers have come up from the sea for the year. This last prayer is made individually, each Ama returning to the mountain in their own time to give thanks.

We pause at the temple threshold to thank Arai-san for allowing us to witness this ritual. She bows, then makes her way down the mountain path, and we agree to meet her again in an hour at Kashikojima Port – a special location for today’s dive, on the northern side of Ago-wan, where diving doesn’t normally take place – bringing forth the temple’s blessing into an afternoon on the water.

We follow the same road, passing bamboo thickets and stone markers, until the sea returns in a wide sheet of light and the harbour of Kashikojima comes into view. Its waters spread in broad planes of pale blue, and the boats along the quay knock softly against their ropes. On a small jetty, Arai-san waits with her fellow diver and elder, Kimiyo Hayashi, in her seventies, along with their boat captain. Their presence feels steady and companionable, formed by years spent working these waters together.

“Before heading out, I make sure I am fully calm, as finding things under water takes focus. Worries break concentration, so I keep the morning slow to prepare for the dive.”

The two women wear long-sleeved white diving tops and black trousers in a sleek scuba fabric. Their gloves lie bright on the bench – saffron orange, soft from use – and their hoods rest loosely around their shoulders until the moment of preparation. Hayashi-san’s hat is patterned with small flowers, its brim shading her face; Arai-san’s hair is tied in a simple braid, the end tucked neatly behind her.

Before boarding, Arai-san shares how she prepares for each dive. She keeps her mornings slow, knowing that searching underwater requires a peaceful mind. “Before heading out, I make sure I am fully calm,” she says, “as finding things under water takes focus. I avoid any mental bustle as much as possible. Worries break concentration, so I do what I can the day before and keep the morning slow to prepare for the dive.”

Prior to entering the water, the Ama convene at their local hut – into which we will be welcomed later today – to warm themselves by a fire, a gesture for the body and an old form of protection that has remained part of the routine. A third ritual follows at the cusp of each dive, known as ‘nezumi-naki’, or ‘mouse calls’, for which the divers usually shout ‘tsui, tsui, tsui’ and tap the edge of the shore or boat three times to protect against evil spirits. “When we step off the boat: we call out ‘tsui’ or ‘tsuyo’ as we enter the sea. It’s a habit, more than a prayer, almost like a battle cry, though it likely began as a wish for a big catch,” she tells us. “Now it feels like custom.”

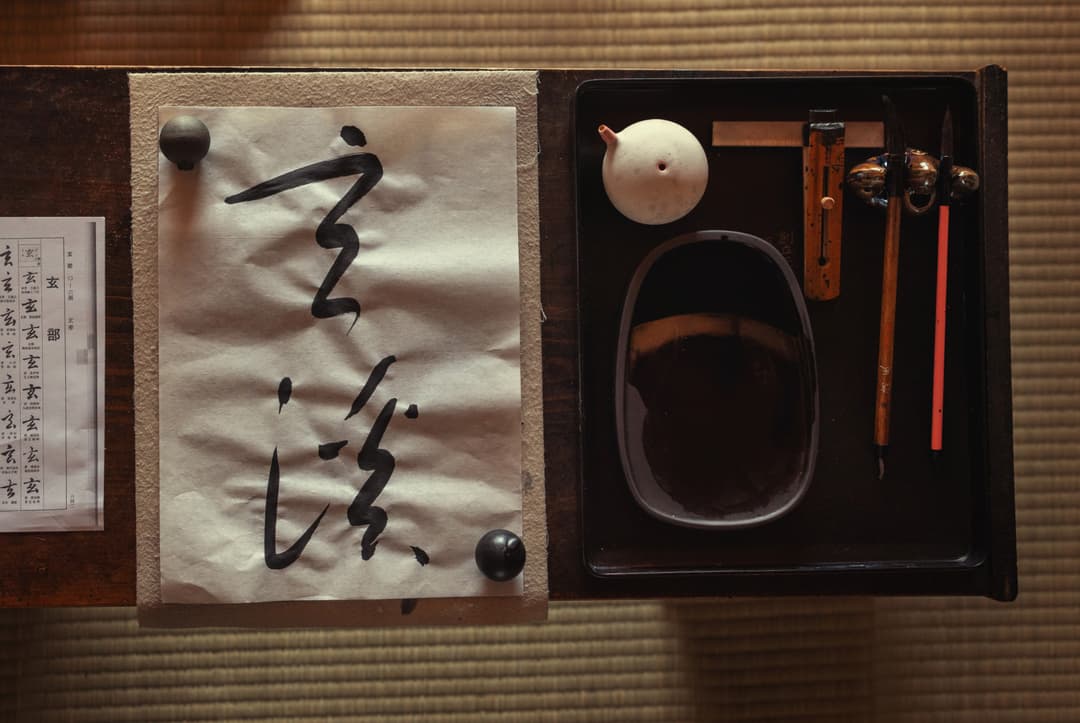

Their masks, with their wide circular lenses covering eyes and nose, are linked by delicate metal chains which give them a jewellery-like quality. Wooden gauges rest in a shallow tray, ready for measuring shells. She returns to a memory from her early days in the water. The first time she dived, she was nervous, surrounded by other Ama, watching and copying their movements. “What struck me most was a huge seaweed called ‘sagarame’, and countless turban shells were clinging to it, like apples on a tree. I remember thinking how beautiful that sight was.”

“When we step off the boat, we call out ‘tsui’ or ‘tsuyo’ as we enter the sea. It is a habit, more than a prayer – almost like a battle cry – though it likely began as a wish for a big catch. Now it feels like custom.”

Soon, the captain gestures. The engine murmurs to life. The Ama board their boat and take their places on its narrow bench, facing the open water, ready to set out toward their diving grounds. We climb aboard a separate vessel, which follows the Ama boat as it moves away from the harbour. The engine purrs, interspersed now and then by the shifting of the glossy water against the hull.

Ago-wan opens around us into a scatter of small islands and distant rafts. Rows of buoys mark the pearl farms, each line holding oysters beneath the water, the cultivation work once done by Ama hands long since shifted to industrial methods. The air has a faint mineral edge and the scent of algae drying on the rocks. Arai-san and Hayashi-san prepare with minimal speech – a glance, a nod, a small lift of the chin.

The water is warm today under 25-degree air. Its sheen lifts and settles as Arai-san and Hayashi-san step feet first into the sea. Their descent begins with a sharp, audible inhale – the signal that the dive has started. A rope trailing from the stern keeps them connected to the boat, a single, dependable line between sea and surface. They will remain in the water for about an hour, working through their search with practised ease, and resurfacing every one to two minutes for a deep gulp of breath. Below, visibility opens in shifting greens and muted golds. Arai-san keeps to around 6 metres when taking turban shells or abalone, moving slowly along the rocks where the shells anchor themselves.

The yearly harvest begins on 1 May, the date fixed within the local association of Shijima that the pair belong to. Other districts open earlier, but Shijima is among the latest, which sees the season run for four and a half months. During that window, abalone and turban shells form the main part of the harvest. Across Mie Prefecture, regulations prohibit taking abalone from 15 September to 31 December.

Back on the shore, the Ama will carefully measure each shell with a handmade wooden gauge to ensure they exceed the required size: 2.5 centimetres for turban shells, 10.6 for abalone. In the past, traditional measures known as ‘sun’ guided them, ensuring each creature has lived through a full cycle of growth before it leaves the sea. These requirements were determined by each village until the Edo period, but are now regulated by prefectural authorities, which differ from region to region.

Their work expands and contracts with the year. Sea urchin – specifically the red urchin – reaches its prime when the roe fills out from late June to mid-September. Seaweed has its own cycle; they gather wakame underwater, though most other varieties are collected, half-submerged, in the shallows during March and April. Winter shifts the pattern again: ‘namako’, or sea cucumber, draws them down to 9 metres, where the water cools and the daylight dims. Smaller shellfish appear throughout the year, though these are left until they grow larger. The practice is built on waiting as much as taking.

From the boat, we watch the work unfold. Each dive its own shape: the flip downward, the soft thud of the life ring settling, the rope tightening slightly as they move. Flippers break the surface first when Arai-san rises. She hauls herself back aboard in a clean motion, water streaming from her suit. Only once she is fully on deck does she lift her mask away. Hayashi-san emerges soon after. The boat rocks as they settle in, and the water around us closes again over the place where they vanished moments earlier. Their catch rests in the net: a small haul of turban shells, thick and spiral-ribbed, and some hiougi shells, a type of scallop, still rough with kelp and grit from the rocks.

“What struck me most during my first dive was a huge seaweed called ‘sagarame’, and countless turban shells were clinging to it, like apples on a tree. I remember thinking how beautiful that sight was.”

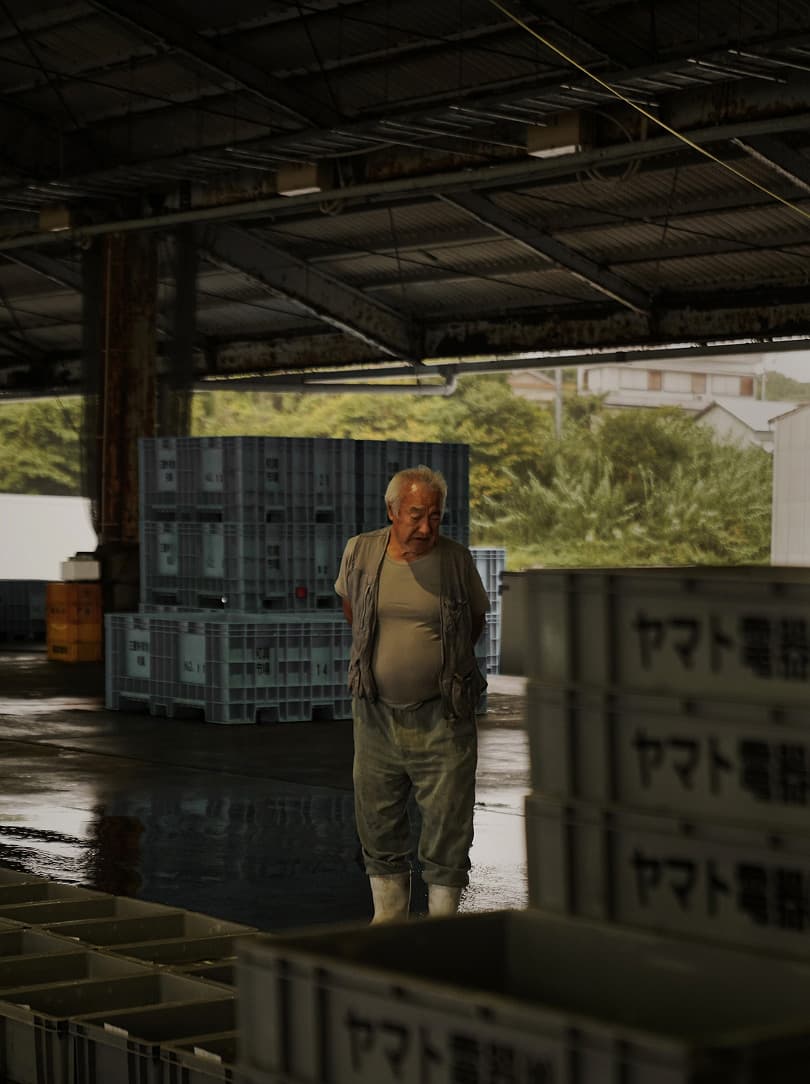

From the water, the route back to shore is familiar to every diver. The catch – sorted, measured and rinsed – travels with them towards the port market, the hub where the Ama and fishermen bring whatever the tide has allowed that day. The harbour sits open to the bay, its concrete quays slick from seawater and the steady movements of boats unloading their trays.

Under the A-frame roof of the open-air hall that frames the port and its makeshift marketplace, grey crates sit in loose grids across the ground while thin runnels of water thread between them. In the central office, binoculars rest on a ledge for scanning the horizon, while outside a barrel fire sends up a coil of smoke and the drains release deep, tidal gurgles underfoot.

Buyers in white boots crowd around the auctioneer, their hands gripping wooden bidding blocks. Heavy with anticipation, the air is tinged with salt, metal and the faint tang of fish scales drying on the concrete. Boats carve through the water returning from their pre-dawn departures, some replete with abundance, others with a single fish. Each approach draws a subtle stir among the buyers.

We witness the brief rush that follows the arrival of a Spanish mackerel, 17 kilos of silver weight lifted from the tray with practised assurance. The price peaks at 8,500 yen. Once agreed, the fish passes quickly from tray to bucket to the hands of the buyer. A forklift moves in with a load of ice, its low hum rising toward the steel rafters.

Many of those working here divide their days between fishing and other trades – carpentry among them. Auctions run twice daily – morning, then again mid-afternoon – each round drawing a small crowd from nearby hamlets. Ama divers weave into this scene, sometimes arriving by boat, sometimes by bike or small truck, adding their own haul to the market’s flow. “What counts as a big catch depends on the person,” Arai-san notes. “The entire amount you catch becomes that day’s earnings.” Footsteps on wet concrete, the knock of crates, the boom of forklifts, the distant clatter from the shipyard – the port gathers all of it.

Having witnessed the culmination of the Ama workday, we curve round the coast to meet the two women divers at their hut that anchors their community. Every hamlet along this coast keeps its own. These huts serve as a meeting place, shelter, workspace and hearth. They are where divers light the first fire of the day, warm their bodies before entering the sea, prepare their gear, and return afterwards to unwind and recharge. The hut is equally a social world, holding stories, humour and the exchange of knowledge passed down.

“To release the pressure of the water, we must sit by the fire and sweat it out, otherwise it affects our performance the next day. We warm our bodies thoroughly.”

Situated in a modest residential strip between seashore and hillside, fronted by a concrete sea wall and sun-bleached grass, the structure stands low to the ground, patched with corrugated metal and streaked timber mottled by years of salty air. White shirts and cloth hoods hang from a clothesline outside, waving gently in the breeze. Bundles of firewood are stacked beneath a makeshift shed. The air carries a scent of salt and smoke that lingers in the frame of the doorway. Inside the hut, tatami mats border a sunken hearth from which an enveloping heat rises. It holds the remnants of a well-tended fire – warm ash and a wire grill pulled over glowing coals.

“Inside the Ama hut, the main purpose is to light a fire and warm our bodies by it,” Arai-san explains as she arranges herself beside the pit, now in black cotton trousers and a turquoise wool sweater. “To release the pressure of the water, we must sit by the fire and sweat it out, otherwise it affects our performance the next day. We warm our bodies thoroughly.”

Wearing grey trousers and a striped long-sleeve shirt, a white towel looped round her neck, Hayashi-san crouches by the hearth, deftly adjusting the logs. She began diving at 15, and her movements reflect a lifetime spent in this rhythm of sea and fire. The heat rises around us as she lifts white mochi over the embers. This type needs constant turning to avoid burning, so she rotates each piece carefully, as the surface blisters and stretches.

Voices flow easily across the room. The conversation moves between tales from the water and remarks on life in the hamlet. “From the senior divers I dive and share the hut with,” Arai-san says, “I’ve learned not only about diving, but also about our district – stories about people I’d never met, and even lessons in farming and local life. They act as mentors.”

Hayashi-san’s own path spans oceans. She worked for two years in the United States as a tourism Ama, diving in theme-park water in San Diego, Los Angeles and Ohio, offering visitors akoya oysters with pearls inside. Returning home brought her back to the real sea, with its shifting moods and work that demands attention rather than performance. Now she speaks of diving without drama. It steadied her, she says, easing stress and offering a sense of emptiness that felt right.

She has watched the coast change. Rising temperatures have thinned the seaweed beds that once supported abalone and turban shells. Stocks have dropped. The number of active divers has dwindled. Many who once met here daily are gone. She remembers when groups headed out together at 8 in the morning, returning later with the sun behind them. The feeling was communal. Today, she is often the only one here.

Hayashi-san checks the coals, deems the mochi ready, and offers us one. A crisp outer shell gives way to a warm, chewy interior, its texture fortifying. The warmth wraps around our shoulders, the sound of the shoreline drifting in through the open panels. The hut feels like a hinge between land and water, holding the shifting texture of a way of life that is growing increasingly fragile.

For Arai-san, the meaning of her work begins in the water itself. “To me, the sea is an important place where I earn my livelihood and also one of my reasons for living, my ‘ikigai’,” she tells us, referring to the concept of a guiding sense of purpose. “I came here because I wanted to become an Ama diver, and working as one has become my purpose in life, so in that sense it is a place I cannot live without. It is my livelihood and my passion.”

“To me, the sea is an important place where I earn my livelihood and also one of my reasons for living, my ‘ikigai’.”

The anticipation she feels before each dive is tied to the uncertainty of the day: “When we go out to dive, it depends on the ocean conditions, but I feel excited, wondering what kind of catch I’ll encounter and what kind of diving I’ll be able to do. There are days when the waves are high yet I say, ‘I’m going anyway’, as long as I can judge that it’s still safe; or when the water is cloudy, but I tell myself there will be a catch and I psych myself up. Some days require real determination.” Her work moves with the state of the sea: shifting grounds, altering targets, noticing changes that appear gradually until they feel sudden.

Among these shifts, the patterns of the Kuroshio Current draw attention. In 2017, the Kuroshio – a warm, fast-moving current along Japan’s Pacific coast – entered a long-lasting ‘large meander’ path that has altered water temperature and brought unfamiliar species into these bays. Its change has been gradual yet noticeable, influencing the rhythms of local fishing and the divers’ search for abalone.

The consequences show themselves in specific ways. “Abalone had high value and were my main catch, but with them gone I now take turban shells, so my earnings have decreased,” Arai-san shares. She has watched entire beds of kelp vanish, their disappearance a clear sign of rising temperatures and an unsettled marine world. Her worry has weight: climate change is reshaping the sea the Ama depend on, thinning the habitats that once sustained both the divers and the life they harvest. “I think something similar could happen on land,” she posits. “I want people to imagine that possibility. I want to communicate that this is already happening.”

“One thing I’m worried about is that the wisdom accumulated by the Ama, who have maintained this tradition, might disappear once they are gone. We need measures to preserve it.”

The future of the Ama is linked to these waters, and the number of divers reflects the health of the sea. “I think the condition of the sea and the number of Ama divers are proportional. Few young people are starting careers as Ama divers; people see that it’s difficult to earn enough income from the sea directly in front of us, so few choose this path.” The knowledge that has sustained the Ama for centuries feels at risk. “One thing I’m worried about is that the wisdom accumulated by the Ama, who have maintained this tradition, might disappear once they are gone. And if new people start freediving to make a living later, there will be no way to pass it on. We need measures to preserve it.”

We leave the warmth of the hut and walk out into the late light. The fire’s scent lingers on our clothes as we descend towards the shoreline, the water glinting through breaks in the trees. On the road out of Shijima, Arai-san’s words return: “I think a new generation may wish to become Ama divers someday. If the sea improves, more people will want to follow this path.” Her outlook carries the same patience, the same cautious optimism that guides her work itself – a belief that the sea, if allowed to recover and sustained with respect, will continue to draw divers back into its reach.